|

Porsche: Excellence Was Expected

Price: TBD

|

©2003 Robert Bentley, Inc. We encourage visitors to link to this page if you'd like to share this information with others. Please do not copy this excerpt to other web sites. It is protected by copyright and represents significant resource investment by Bentley Publishers.

(10 page excerpt from Chapter 33)

Chapter 33:

Flat-Out Flat-Sixes

|

|

Year by year the Kremer-modified 935s became more ambitious as the brothers learned how to interpret the Group 5 regulations. In 1981 Bob Wollek competed in this right-hand drive car so successfully that he was the winner of the Porsche Cup. |

|

|

The Porsche 935 and 936 were essentially turn-key racing cars that customer teams could buy and immediately race. Essentially a heavily-developed Porsche 911 with twin-turbo 2.8-liter engine, the 935 was capable of challenging for overall victory. |

"Porsche Wants to Be Your Race Car Company." That's the way Car and Driver headed its story on the 1977 Watkins Glen 6-hour race. It pointed out that of the 44 competitors at the Glen for both world championship and SCCA Trans-Am points, 21 were Porsches. Of those 21 Porsches, 17 completed the race. And Porsches filled the first dozen finishing positions and took three class victories.

For the works 935/77 that was airlifted to the race at Watkins Glen ($1,088 one-way), C/D estimated a cost of $11,200 to ship the 11 tons of spare parts that accompanied the car-only a small portion of Porsche's entire budget for the expedition to upper New York state. Yet the total prize money payable to the top dozen Porsches at the finish was only $35,000. "In this light," said the magazine, "Porsche appears to be subsidizing American racing."

It wasn't Porsche's fault that it came to dominate sports car racing both internationally and in the United States at the end of the 1970s. In their wisdom the FIA's rule makers had decided to bring their sport closer to the standard car with their new Group 4 and 5 regulations. Where standard sports cars were concerned there were few auto makers who could hold a candle to Porsche.

Porsche hadn't asked to be so dominant. It relished competition and had expected to be racing against entries from Corvette, BMW, Jaguar, Alfa Romeo and others. Built from scratch for racing, BMW's mid-engined M1 coupe was a much-feared challenger in Groups 4 and 5. However it fell behind schedule and failed to reach the track while the rules to which it was built were still in force. Other contenders in the national and international classes couldn't stand up to the speed and durability of the Porsches—powered by the potent turbocharged flat six.

Mighty 934

Closest to the standard Porsche Turbo, the 930, was the Type 934. It qualified for entry in Group 4 racing by virtue of the fact that Porsche had met its criterion of making 400 cars in two consecutive model years. Porsche made 31 race-prepared versions of the 934 and supplied components to owners of roadgoing Turbos to convert their cars as well. Such a Porsche-built car was complete and ready to race when it left the factory, said Rolf Sprenger, who ran the works service department that carried out many of the conversions for customers, "On one occasion we took a 934 to the Nürburgring, still with the plastic covers on the seats, and it was instantly competitive."

|

|

In American racing the Group 4 Porsche 934s continued to be as useful in several series as they had been in 1976 when this SCCA Trans-Am race start took place. George Follmer was in number 16 and Hurley Haywood in number 0. |

|

|

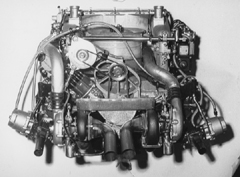

Engines for IMSA 934s had to retain their standard air/water intercoolers but could be extensively modified otherwise. In this example the circulating pump for the intercooler's coolant is driven from the camshaft on the left side of the chassis. |

The 934 was the logical successor to the Carrera RSR; it was also a quarter-minute quicker around the Nürburgring's North Loop. Because the 934's aerodynamic fittings and rear-tire widths were constrained by the Group 4 rules, this turbocharged Porsche was considered a handful to drive. "I thought the 934 was quite a nasty little car," said Derek Bell. "With the engine overhanging the rear wheels, it felt a quite spooky proposition." Enough drivers mastered it, however, to make the 934 the car to beat in the GT category and in its class in SCCA Trans-Am racing in 1976, where George Follmer was champion in one of Vasek Polak's five 934s.

IMSA in America admitted the 934 to its series from 1977. In IMSA competition the car was allowed wider rear wheels and a larger rear wing, which made it much more drive able. Porsche produced ten cars to this new specification which became known as "934½" models. One remained in Europe and the others were sold to US racers. These cars also had the benefit of Bosch plunger-type fuel injection replacing the K-Jetronic system, which increased the horsepower of the 3-liter Type 930/73 engine to 590 bhp at 8,000 rpm.

As required by the rules, the 934 kept its single turbocharger, which in spite of Porsche's sophisticated manifolding often lagged behind the driver's need for power. "The single-turbo cars were a handful with all that turbo lag," UK racer Nick Faure told John Starkey. "Jacky Icxk told me to commit the car to the corner and saw away at the steering wheel to scrub off the speed while not lifting your right foot. I mastered the technique but it took a lot of bottle to start with!" Another successful 934 advocate was Britain's Richard Cleare. "The turbo lag was tremendous," he said. "You couldn't afford to waver on the throttle through the corners, even for a fraction of a second, or you'd lose it for the whole of the next lap. It was hard work in slow corners."

In Europe, the 934 was the Group 4 category winner at Le Mans in 1977, 1979 and 1981. In fact, in the 1979 24-hour race a 934 finished fourth overall, driven by Herbert Müller, Angelo Pallavicini and Marco Vanoli. They were no less than 30 laps ahead of any Group 4 rival. The 934 was the FIA GT Cup winner in 1978. These were rich returns from a modest conversion of the production 930 Turbo, which was testament to that car's excellent engineering.

Upping the Ante—and the Boost

Returns were richer if anything from the advances that Porsche made with the 935 in Group 5 during the 1977 season. Already massively powerful, its engine was given improved turbo response by replacing the single unit with two smaller KKK turbochargers, each of which had its own waste gate—as used in the standard 930. The Type 935/77 engine—for the car of the same designation—developed a nominal 630 bhp at 8,000 rpm on a boost of 20 p.s.i. Its maximum torque output was a robust 434 lb-ft at 5,400 rpm.

To improve reliability for a 24-hour race, the boost could be run as low as 18 p.s.i. In sprint events, racers used higher boost; for example, 22.7 p.s.i. might be used during qualifying, while 21.3 p.s.i. would be selected for racing. The rev limit of 8,000 rpm was strictly observed. In endurance races, canny drivers observed a 7,400-rpm limit in top gear and 7,200 rpm in the lower ratios. Shifting was done with care, by depressing the clutch fully and making a slow, deliberate shift to avoid over-stressing the synchronizer rings.

Placed at the back of the engine, the turbos pumped pressurized air forward to a new water-cooled intercooler located at the front of the flat six. Space for this had been made available by one of several Group 5 rule changes for the '77 season. One was that the firewall between the engine and the car's interior could be moved 20 centimeters, almost 8 inches, toward the interior. Norbert Singer, developer of the 935/77 model, used this space to install the intercooler. Another new rule said that the car's floor could be raised to the level of the door sills to make more room for turbo exhausts for front-engined cars.

The FIA's new rules also defined the car's "body structure" as the metalwork between the front and rear bulkheads. This gave Singer the freedom he needed to lengthen the front suspension wishbones from 27.8 centimeters to 34.1 cm, and to raise their inboard pivots by 37 mm—thus diminishing the camber change caused by jounce at the front wheels. Unsprung weight was reduced by replacing the standard vertical strut with a lighter part of aluminum with a magnesium hub carrier. Coil springs could be either steel, at $110 apiece, or lighter titanium at $780 each.

A typical suspension setup for the 935 used front springs with a rate of 380 lbs/inch and stiffer rear coils needing 580 lbs/inch to constrain the movement of the rear trailing arms and improve traction. Cockpit adjustability for stiffness was provided for the front anti-roll bar instead of for the rear one, as had previously been the case. This was more effective in relation to the less-stiff front-wheel springing. Roll-bar diameters were 14 mm in front and 26 mm in the rear. Facing the driver were lights that warned of failure of the fuel pressure, oil pressure, cooling fan and generator, as well as electronically controlled lights that signaled the boost pressure.

|

|

Porsche's development of its own 935/77 for the 1977 season produced significantly improved aerodynamics with a reshaping of the tail, reducing drag by 10% while maintaining downforce. |

|

|

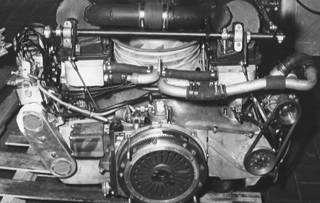

The major change to the engine of the 935/77 was the adoption of twin turbochargers to assist both power and throttle response. Output of this engine was 630 bhp at 8,000 rpm. |

Stopping this Group 5 projectile was as important as accelerating. As a result, brakes of 917 type and size continued to be used. Pedal pressure was reduced by fitting a 930-type brake-booster servo between the pedal and the dual master cylinders with their adjustable balance bar. This was much appreciated by the drivers, but the servo was discontinued during the 1977 season after it was found virtually to double brake-pad wear. In its stead, to lighten the pedal pressure, the 38 mm rear-brake calipers were replaced with the same 43 mm cylinders—four per caliper—as at the front. These big brakes fit inside wheels with rim widths of 11 inches in front and 15 inches in the rear. The respective diameters were 16 and 19 inches.

A servo was also experimented with over the winter to assist the 935's steering. Although this was never raced, according to racing director Manfred Jantke it led to improvements in the manual steering. "The steering had a new geometry pattern after the power-steering experiments and it's beautiful now: just like a Rolls-Royce!" Another development during 1977 was the introduction of Porsche's own wheels to replace the BBS parts which, Jantke said, "lost air because of the leverage cracking the separate centers from the rims. It has been very expensive for us, but we have made our own Porsche wheel."

|

|

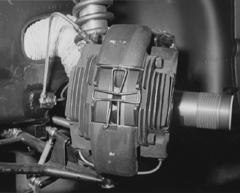

Massive brakes with cooling fins on the calipers were fitted to Porsche's 935/77. During the season a brake servo was experimented with but ultimately not pursued. |

Over the 1976-77 winter Norbert Singer was busy in the wind tunnel, including VW's full-sized one at Wolfsburg, enhancing the 935's aerodynamics as much as the Group 5 rules would allow. That he was successful was indicated by the fact that the new car generated the same downforce as its predecessor, with 10 percent less drag—a coefficient (Cd) of 0.393 instead of 0.435—with similar frontal area. This was achieved by the complete reprofiling of the rear of the body with added-on glass-fiber surfaces including inlets for intercooler air. The new body panel had its own rear window above the original one, which the rules required to be left in place—although it could be, and was, made of Plexiglas.

Porsche built three new cars to this ambitious specification for its Martini-sponsored factory team in 1977. In fact, it might have eked out the year with two cars had not one of them been written off in its first outing in the Mugello 6 Hours in Italy on March 20. Driven by Jochen Mass and Jürgen Barth, the brand-new car led the race from pole. It crashed with Barth at the wheel following the second hour, immediately after a pit stop during which the brake pads were changed. Finding no stopping power at 120 mph, Jürgen took out a competitor in the subsequent crash. The incident also contributed to Singer's abandonment of the servo brake system.

The first 935/77 built, the development hack, was raced only once by the factory, winning at the Norisring in the hands of Mass. After the Mugello crash a third car was rushed to completion in time for the important Nürburgring 1000 Kilometers. This car, chassis 005, was crewed by the exceptional team of Jochen Mass/Jacky Ickx. They took it to victories at Silverstone, Watkins Glen and Brands Hatch. These triumphs combined with successes in the other qualifying races by private Porsches to bring the 1977 world championship for makes to Zuffenhausen. An important non-championship race contended by the 935/77 was the 24 Hours of Le Mans. There Rolf Stommelen and Manfred Schurti drove a lone example geared to reach 83 mph in first, 121 in second and 145 in third. Its top speed on the long straight was timed at 201 mph. It was forced to retire by the failure of a cylinder-head gasket, even though it was running at the relatively low boost pressure of 18 p.s.i. for the sake of durability. With this fault also afflicting the 935/77 in shorter races, where boost was 21 p.s.i. to produce 650 to 680 bhp, Porsche's engine men were given some food for thought.

Thinking Small: 935/2.0

A more immediate challenge to Hans Mezger and his engine team was laid down by Ernst Fuhrmann in April of 1977. His Porsches were dominant in Division 2 of the popular German sports-racing championship, while in Division 1, limited to 2 liters, Ford and BMW were enjoying some ding-dong battles—having given up any attempt to take on the Zuffenhausen cars in the big class. Fuhrmann was frustrated by the way these big car makers were shrinking from a clash with his cars, and when he heard that the big Norisring races on July 3 would only be televised in the small category, this was the final straw for the competitive Porsche boss.

On April 5 Fuhrmann signed an order authorizing the building of a special Porsche to compete in Division 1. Remaining true to their latest expertise the engineers decided on a turbocharged entry. This meant a displacement of 1,425 cc (71 x 60 mm) which multiplied by the FIA's turbo fudge factor of 1.4 gave 1,995 cc. With a 6.5:1 compression ratio and 20 p.s.i. boost from a single KKK turbo the six produced 380 bhp at 8,200 rpm. Both valve and port sizes were reduced to suit the diminished displacement. The engine's simple and light air/air intercooler used an exhaust-augmented jet to help encourage its cooling-air flow, recalling the jet-cooled engines Porsche experimented with in the 1950s.

Although based on the 935/77, the new car had to be brought down to the minimum weight for a 2-liter car of 1,599 pounds. "This was exactly 141 pounds less than the lightest 911 ever built to that date," wrote Paul Frère, "the 'Tour de France' car of 1970." It was also a good 400 pounds lighter than an unballasted 935/77. This drastic dieting was aided by the new rules interpretation concerning the car's "body structure". Taking full advantage of this, Norbert Singer chopped off all the body structure outside the front and rear bulkheads and replaced it with frames of aluminum alloy tubing. These were bolted to the body, which had its own stiffening aluminum roll cage.

|

|

At the wheel of the works 935/77 Jacky Ickx (driving here) and Jochen Mass scored three victories in championship-qualifying events, leading Porsche to that year's makes trophy. |

|

|

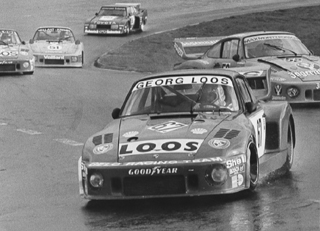

Driving this Porsche 935 entered by the George Loos stable, Ralf Stommelen was the German sports-racing champion of 1977. Other Porsches and a Toyota were among his rivals. |

|

|

“Baby” was unsuccessful in her first outing but at Hockenheim in August 1977 she ran away from the field in the hands of Jacky Ickx. Porsche convincingly demonstrated its mastery of yet another class of racing. |

As for the body itself, said Manfred Jantke, its "steel is the lightest we could use: thinner than before. The bodywork is much, much lighter with the thinnest glass and plastic. Then we have the smaller wheels and really incredible things: the gas pedal is titanium and so is the gear lever. We saved the weight of piping for the oil cooler by placing it in the rear." The engine's reduced power meant that the lighter Type 915/50 five-speed transaxle from the racing 911 Carreras could be fitted. Like the bigger 935s this 935/2.0—nicknamed "Baby"—had no differential. Instead a solid spool joined its two axle shafts together.

Only two months after conception "Baby" first appeared on the day before practice for the Norisring race, turning a few laps at Weissach to make sure she worked. But when practice began on the 2½-mile circuit at Nuremberg, in the shadow of the huge stands that had provided a backdrop for Adolf Hitler's orations, problems arose. Low-speed turbo response was poor and gear ratios were much too high, so Jacky Ickx was only able to qualify 13th among the Fords and BMWs.

On a sunny and hot midsummer day Ickx forced his way to the first half-dozen in the race but soon began to miss a certain amenity. Astonishingly the Porsche engineers had made "Baby" 34 pounds underweight, so she had to be ballasted to bring her up to the limit. One of their weight-saving measures had been the substitution of thin glass-fiber for the steel firewall that previously separated engine from driver. Ickx soon paid the price for that change as cockpit temperature soared to 50° C. At that level, said Jantke, "the human body cannot breathe properly and we had to stop racing that day because Jacky could not drive any more."

This withdrawal was disappointing to Fuhrmann, Helmuth Bott and their engineers, but they realized that they hadn't had quite enough time to get "Baby" ready. They fitted an insulated firewall, cut new gear ratios, stiffened the body and frame and reprofiled the fuel-injection controls to improve engine response. It was still less than brilliant. A later driver found little urge below 6,500 rpm and "rocket ship" power above that to more than 9,000 rpm. By the time of the German Grand Prix in August the 935/2.0 was ready to be entered in the Division 1 supporting race at Hockenheim.

This was payback time for the petite Porsche. Ickx qualified it on pole with a margin of more than two seconds and ran away with the race to finish half a lap ahead of Hans Heyer's Ford Escort. It was a compelling demonstration in front of the huge crowd attending a Grand Prix weekend. Having proved its point—that it could win in this class if it wanted to—Porsche retired the Baby to its works museum.

"This is not a real Porsche," said team manager Jantke about the 935/2.0 afterward. "This car was built to prove one thing: that we are better than the Fords and BMWs which are in this class in German races. We do not belong in this class now. All our road cars are 3 liters and more. It has taken us 20 years to move up from 1,100 cc to the present, where we can win outright. We are not willing to go backwards."

Mastering the 935

Winning outright was certainly now the hallmark of Porsche's racing efforts and the 935 was making a strong contribution to that status. It was the product of the investment in motor sports that Porsche made in 1977, amounting to between four and five million Deutschmarks—around $2 million and less than half a percent of the firm's turnover. Added to this was the fee of two million marks paid by major sponsor Martini for the right to have its distinctive and attractive colors on Porsche's racers.

For the 1978 season Porsche abstained from works competition at the national level, reserving the right to compete in the big international events. For the private teams on which Porsche increasingly relied, its service department built 15 new 935/77 racers with twin-turbo 2.8-liter engines for 1978. Seven more cars were made for the 1979 racing season. The '79 cars had a new inverted mounting for the transaxle that was implemented to reduce the angularity of the half-shaft universal joints. The repositioning also made it easier to change gearsets to adapt the 935 to different circuits. According to Porsche, it built 35 Type 935 racers over these seasons.

In the meantime, the works engineers had come up with a solution for the cylinder head-joint failures that had caused several retirements in 1977. Instead of the previous hollow copper sealing ring they fitted a plain steel ring into matching grooves in the head and the top of each cylinder. Thanks to this technique they were able to offer their customers reliable engines up to 3.2 or 3.3 liters (95 or 97 x 74.4 mm) in capacity, a size that was mainly used for the sprint races in the German sports-racing championship. It was not unknown to qualify with a 3.2-liter engine and install a 2.8-liter six to get better fuel economy in a race. Keeping oil temperature low enough was a problem with the biggest versions.

Reliability was improved by the better fuel metering provided by a Bosch electronic control for the mechanical Kugelfischer fuel-injection pump. Still running to speeds as high as 8,000 rpm, these 3.2-liter engines produced as much as 800 bhp on a compression ratio of 6.8:1 with 24 p.s.i. boost—a pressure suitable only for short-distance events. With his cockpit handwheel the driver reduced the boost pressure to 21 p.s.i. after the start and to as low as 18 p.s.i. for a long race like Daytona or Le Mans. At the lower boost level, output was still strong at 740 bhp at 7,800 rpm.

With the cockpit boost control, wrote Brian Redman in Road & Track, "it was a real art to extract the maximum from these engines without blowing them up." When racing a 935, Redman had been told by its owner not to touch the boost wheel. After some disappointing qualifying efforts, however, he "decided to ask the opinion of a real Porsche expert. Going to Rolf Stommelen, I said, "Rolf, do you ever touch the boost in qualifying?" Standing with his feet apart, head thrown back and laughing, he replied, "Brian, do I ever touch ze boost? I turn it as far as it vill go!"" That meant two atmospheres of boost or 28½ p.s.i.

Gianpiero Moretti of Momo wheel fame owned one of the teams racing the 935, and when he gave Road & Track's Joe Rusz a ride in one at Daytona and opened the throttle "the car responded in what seemed like a great bound—like the leap to hyperspace in Star Wars." When he came to drive one himself at Road Atlanta, Rusz wrote in R&T that that "the 140-mph shift into fourth in the Porsche wallops the driver in the small of his back and snaps his head back. Acceleration continues strongly the whole length of the straight.

"On the straight you also come to understand turbo lag," added Rusz. "At moderate engine speeds throttle response is instantaneous. At 7,000 on the straight, lifting out of the throttle pops the turbo off, and there is perhaps a second of coasting between the time the driver flattens the accelerator and acceleration comes back." "It gradually developed better track manners," Derek Bell recalled, "and was always a bit tricky with that engine hung out at the back, but it had a lot of sheer grunt and terrific brakes. It really stopped superbly."

"You had to be really paying attention," said driver Hurley Haywood, "but when you got the hang of driving them, they were fantastic. You had to pitch 'em into the corner and slap the gas down. Everybody had their own particular style, so a fan could tell whether Danny Ongais was driving or Peter Gregg or Hurley Haywood or John Fitzpatrick or Bob Wollek."

"It was a very comfortable car to drive," recalled racer and preparer Bob Garretson, "because the seat had plenty of fore-aft adjustment. The seat itself was great. The gear lever was in just the right place, and because there were only four ratios there was no problem with wrong-slotting. The cable-operated clutch was easy to use and not at all heavy, and the front/rear brake bias could be adjusted by the driver." Summed up driver Bob Akin, "The 935 represents the high-water mark of evolution and technology as applied to a production design—proving the old adage, "You can't make a race horse out of pig, but you can make an awful fast pig.""

Porsche ended up with three of these "fast pigs" in its own inventory. One of its 935s was assigned "taxi" duty at Weissach to replace the 917 that had been used for so long to entertain special visitors to the development center. Its designated driver was Rolf Hannes, head of the Porsche test-driver corps. Six-point-belted into the 935's passenger seat were such notables as King Carlos of Spain, Belgium's Prince Albert, Swedish King Carl Gustav, tennis star Martina Navratilova and conductor Herbert von Karajan. Hannes gave the car a check of brakes and tires before each run and a close inspection of its suspension and chassis after every 500 laps.

Among the teams competing with these cars in Europe was that of Georg Loos, a German real-estate developer. "All he actually owned was the transporter and the cars," recalled service chief Rolf Sprenger—"everything else was done by us! The mechanics wore Loos overalls, but in fact he'd hire them for the weekend from us! It was a pretty smart move, actually. If one of the mechanics went sick, or if there were any other problems, it was our worry, not his. Some owners used to get quite jealous and suspicious, and accused the Loos team of being a semi-works outfit, but there was nothing keeping them from doing what Loos had done."

|

|

Driving this Porsche 935 entered by the George Loos stable, Rolf Stommelen was the German sports-racing champion of 1977. Other Porsches as well as a Toyota were among his rivals. |

The Porsche crew at the track was headed by Elmar Willrett, Sprenger's extremely capable second in command. He was, Sprenger told historian Mike McCarthy, also "a brilliant driver, and all the racing cars built by the service department were tested by him first. And if a customer came along complaining that his car wasn't fast enough or that there was something wrong with it, he'd take it out and check. Sometimes it was clear that the only thing wrong was the driver, so he'd have to be careful what he said!"

No such problems arose with drivers of the caliber of Toine Hezemans, John Fitzpatrick, Hans Heyer and Klaus Ludwig, who piloted the Loos-entered 935s to international successes in 1978. One won the first race at Daytona, where five other Porsches joined the winner to form a finishing phalanx to take the checkered flag. More Loos wins followed in endurance races at Mugello, the Nürburgring and Watkins Glen, which was the scene of a thrilling battle that saw Fitzpatrick finish in the lead with little fuel, a half-minute margin and no driver's door. With its other victories, Porsche was the unchallenged makes champion that season.

Top teams learned how to keep their 935s in fighting trim. "We'd run the engines for 30 hours and then strip them for a full rebuild," said Bob Garretson. "That included new valve guides, cylinders and pistons, because we found that the top ring land on the piston would start to deteriorate. We also used to resize and rebush the titanium connecting rods. Most people weren't aware of how much the rods got out of shape. We used stock camshaft-chain tensioners and never had a problem with those. But if you over-tightened the drive belt to the engine cooling fan, the bearings in the right-angle drive would fail."

Keeping the turbochargers alive was no small challenge, Garretson added. "The Germans insisted on using ball bearings in the turbos for less friction. But when the engine was shut off the bearings would get fried because they were suddenly starved of oil, and we'd wreck another turbo. Fortunately my brother worked at Garrett AiResearch, so we used to take the standard KKK units and install sleeve bearings, which all but cured the problem. By the end of our race program we were even using KKK housings with AiResearch internals."

The Kremer 935s

During the 1978 endurance-racing season, when a Georg Loos car was not successful the wins went either to a factory car or to a 935 built by the Kremer brothers. Erwin Kremer was the winner of the Porsche Cup of 1971. With his younger brother Manfred, who looked after technical matters, Erwin and his Auto Kremer Porsche dealership in Cologne built their own racing cars on the stout foundation provided by Porsche. Ultimately their designs became the yardstick for the perfection of the 935. Porsche acknowledged this after 1979 by ceasing to produce 935s of its own—although the odd car could still be made by Sprenger's service department—instead making parts available that Kremer and others could incorporate in their cars.

|

|

At the Nürburgring in the ADAC-Goodyear 300, ten Porsche turbos are led by Bob Wollek in the Number 2 Kremer-Porsche 935. |

Starting in 1977 by modifying a 934 into a "K" version, the Kremers wrought their own changes to the basic car. They started on a radical redesign of the 935 in June 1978. Seven months later when the 1979 season opened, Kremer was ready to introduce its own 935 K3 interpretation—with Klaus Ludwig at the wheel—at the German sports-racing championship event at Zolder.

A major change in the engine room was the use of an air/air intercooler instead of the standard water/air unit. Kremer considered that the water/air intercooler was both heavy and susceptible to a loss of cooling efficiency when the engine was run at high power for an extended period. The air/air replacement fitted into the extra space provided when the bulkhead was moved forward as the rules allowed and used the engine's cooling fan to suck some of the air through the intercooler. Kremer quoted 805 bhp at 8,000 rpm with a 6.8:1 compression ratio for its engines. Quick response from two KKK turbochargers helped the boost come in as low as 5,000 rpm to improved driveability.

Close attention to detail in the car's structure helped make the K3 stiffer than other 935s. Almost 100 linear feet of aluminum tubing were welded into the internal roll cage, which was attached to the body at 12 points. Aluminum tubing formed a front-end extension to carry the bodywork and oil cooler. The Kremers aimed to shift more weight forward with the 31.7-gallon fuel tank, 5.8-gallon oil tank, battery and brake booster all in the front compartment. At the rear, the engine was carried in another tubular lattice that facilitated its quick removal and repair. Front/rear weight distribution of the 2,260-pound racer was 45/55 percent.

Lightness was added by making the entire exterior skin of resin reinforced by Du Pont's Kevlar 49 aramid fiber. In the process, the body weight was reduced—from the 154 pounds of the usual glass fiber version—to 88 pounds, while the price of the body increased ten-fold. Both intuitively and by running tests on the road with their previous cars, the Kremers also improved the 935's shape. Wide and deep "running boards" followed the design of the works 1977 car to control airflow under the chassis. Flow over the rear deck to the wing and into the engine bay was improved and high fences flanked the front deck to increase downforce. The front skirt, given a scooped profile to the same end, had the headlamps set into its curved corners to produce the K3's distinctive appearance.

"All the racing experts think that our car contains some kind of big secret," said Erwin Kremer, "but sadly there is no such secret. We've always been optimally prepared, for each race installed a freshly rebuilt engine and improved various details—that's all." Compared to a works car, Manfred Kremer told Paul Frère, the K3 incorporated some 100 changes which, he said, "add up to a one percent more efficient car, which is all you need to beat the opposition."

The opposition took a licking from the first 935 K3, which Klaus Ludwig drove to the 1979 German sports-racing championship with 11 wins in 12 races. Astonishingly, as well, the talented Ludwig was joined by the American Whittington brothers, Don and Bill, to win the Le Mans 24-Hour Race that year by outlasting rivals that included works Porsches and Loos entries. They took the lead at 25 minutes past midnight and won in spite of having to pit for attention to the injection pump.

The K3 was quite a car, as journalist-racer Tony Dron recorded after driving one at Silverstone: "In some ways driving the 935 is like driving a giant racing kart: there's a similar, delicious feeling of direct control over physical forces but, of course, at high speeds the aerodynamics of the 935 are also working in your favor. Balanced like this, drifting on a little opposite lock and accelerating with that tremendous, seemingly endless push from the superb twin-turbocharged engine—well, anything to beat it has got to be something special." It was capable of lapping the Nürburgring in 7½ minutes, which would have won it a place on the grid for the last Formula 1 race held there in 1976.

|

|

Klaus Ludwig sealed the desirability of the Kremer K3 version of the 935 by dominating the German Sport-Racing Championship with it in 1979, winning 11 of 12 events. |

Customers queued to buy copies of the Kremer 935 K3 at up to DM375,000, around $210,000. Including the prototype, 12 were made for racing in addition to conversion kits for standard 935s. The Kremer 935 became the standard Porsche Group 5 competitor in all arenas. A refined version for the 1980 season was the K3/80, and a more radical change was the 935 K4 with a new body shape based on a one-off works Porsche called the 935/78. These cars in turn became a stepping-off point for builders of complete 935s from scratch using tubular space frames. These kept the 935 flag flying internationally into 1984, when a 935J built by Joest Racing won the Sebring 12 Hours.

A spare set of body panels set aside by the Kremers for emergencies came in handy in 1983 when they had a visit from Walter Wolf, a wealthy Austro-Canadian businessman who had entered Formula 1 with Williams in 1976 and formed his own team for the next three seasons, during which the team won three races. Out of racing but still passionate about fast cars, Wolf asked the Kremers to build him a K3—as a road car. Some DM300,000 ($115,000) later, Wolf took delivery of a magnificent Kremer creation in his personal colors of dark blue with red and gold striping.

Equipped to virtually full-race specification, with its Le Mans gearing the road K3 was capable of 210 mph. Some tubing was omitted from the cockpit to allow it to be trimmed with stunning similarity to a standard Porsche, complete with electric windows. Clues to the difference were its speedometer reading to 360 km/h (224 mph) and its semicircle of diodes signaling levels of boost pressure, which reached a maximum of 20 p.s.i. for some 740 horsepower. Unlike the racers with their glued-in screens, the Wolf car had a standard rubber-mounted Porsche windshield to make replacement easier.

Damping rates of the road K3's Bilsteins were set 10 percent softer than those of the racers, with ground clearance increased from the usual 2 inches to 4 inches. Tuning of the car's 3.2-liter six was tailored to road use, with the benefit that its twin-turbo boost came in at 3,500 rpm and continued compellingly until the limiter cut in at 8,200 rpm. A special stainless-steel exhaust system provided a modicum of muffling. When Wolf suggested air conditioning, the Kremers countered with the recommendation that he wear a light-weight shirt. He would have needed one, hustling his potent Alberta-registered K3 across the roads of Europe.

End of excerpt

©2003 Robert Bentley, Inc. We encourage visitors to link to this page if you'd like to share this information with others. Please do not copy this excerpt to other web sites. It is protected by copyright and represents significant resource investment by Bentley Publishers.

![[B] Bentley Publishers](http://assets1.bentleypublishers.com/images/bentley-logos/bp-banner-234x60-bookblue.jpg)