|

Equations of Motion -

Adventure, Risk and Innovation

Price: $39.95

|

Buick Beagle - February 2008

Review of Equations of Motion from The Buick Bugle - February, 2008

Equations of Motion: Adventure, Risk and Innovation

An Engineering Biography by William F. Milliken, Jr

Since you are reading this magazine, you obviously have an interest in Buick and, for most of you that interest likely extends to more than just the automobiles that bear Buick badges. It"s likely that the majority of you are generally conversant with Buick history and lore. Thus you recognize the name Charlie Chayne and perhaps can rattle off that he was Buick"s fourth chief engineer before being promoted to GM vice-president in charge of the all of the corporation"s engineering. You might also recall that Chayne was a real auto enthusiast outside of and beyond his General Motors employment, with a personal collection of significant cars, including one of the six Bugatti Royales

You also likely know that Buick has been associated with various types of racing throughout its history, but I"d hazard a guess that even the most knowledgeable amongst you are about to read for the first time about this particular Buick adaptation to racing. Contrary to what you are probably expecting, a Buick engine is not involved. But Buick does have bragging rights to being the first, documented, successful racing application of a torque converter with its Dynaflow transmission, an adaptation and installation enthusiastically supported by Charlie Chayne.

You"ll learn a bit of the story on these pages, but you can read it for yourself in its fullest form in the same book where I discovered it. That book is Equations of Motion, Adventure, Risk and Innovation; An Engineering Autobiography by William F. Milliken, Jr. Milliken is an engineer, not a writer. Yet he tells his story of a career filled with such an interesting panoply of experiences and people in such an engaging way - and the manuscript was so adroitly edited by Beverly Rae Kimes - that I can honestly tell you it is, without question, the most interesting and well-written of the 50-some-odd books that I read during all of 2007.

The idea of installing a Dynaflow in a racing Type 54 Bugatti had its origins in the prior failures of standard Ford, Mercury, Cadillac and other transmissions in such applications. A chance ride in a friend"s brand new Buick Century prompted Bill Milliken to call Charlie Chayne to ask him if he thought a Dynaflow could be adanted to the Bug. Chayne"s cautiously enthusiastic response was, "Let me talk it over with the transmission boys and I"ll call you back."

The return call came quickly and Milliken describes that Chayne told him, "The installation was definitely a possibility. The combination of the relatively low rpm of the 54"s engine, and a comparison of the weight and rear-end ratios of the Bugatti and the Buick, added plausibility. He (Chayne) had his own estimates of the actual power and torque we could expect from the Type 54: max. power of 20 bhp at 4,000 rpm with 263 lb. ft. torque, and 171 bhp at 3,000 rpm with 300 lb. ft. of torque. He said he would send me a set of prints and a mockup converter." Examining the drawings, doing their engineering and a subsequent telephone consultation with a GM transmission engineer, who is only identified by his surname Coughtry, resulted in Milliken and his team purchasing a Dynaflow and associated components.

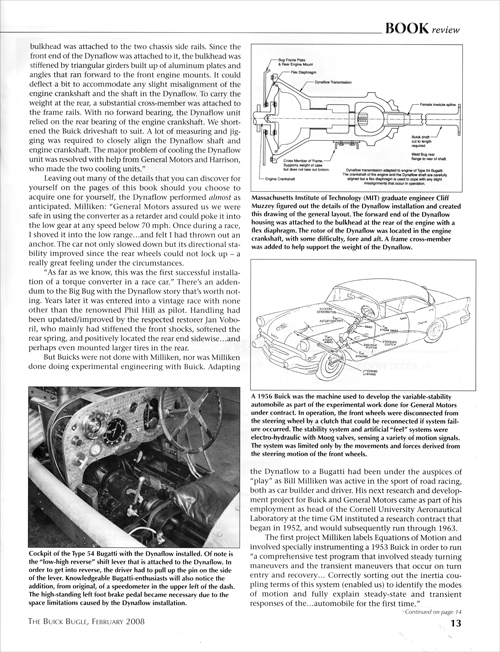

More from Milliken"s narrative: "As the photos and sketches (some of which are shared with you on these pages) show, the installation of the Dynaflow was unique and successful. A large bulkhead was attached to the two chassis side rails. Since the front end of the Dynaflow was attached to it, the bulkhead was stiffened by triangular girders built up of aluminum plates and angles that ran forward to the front engine mounts. It could deflect a bit to accommodate any slight misalignment of the engine crankshaft and the shaft in the Dynaflow. To carry the weight at the rear, a substantial cross-member was attached to the frame rails. With no forward bearing, the Dynaflow unit relied on the rear bearing of the engine crankshaft. We shortened the Buick driveshaft to suit. A lot of measuring and jigging was required to closely align the Dynaflow shaft and engine crankshaft. The major problem of cooling the Dynaflow unit was resolved with help from General Motors and Harrison, who made the two cooling units."

Leaving out many of the details that you can discover for yourself on the pages of this book should you choose to acquire one for yourself, the Dynaflow performed almost as anticipated. Milliken: "General Motors assured us we were safe in using the converter as a retarder and could poke it into the low gear at any speed below 70 mph. Once during a race, I shoved it into the low range ... and felt I had thrown out an anchor. The car not only slowed down but its directional stability improved since the rear wheels could not lock up - a really great feeling under the circumstances.

"As far as we know, this was the first successful installation of a torque converter in a race car." There"s an addendum to the Big Bug with the Dynaflow story that"s worth noting. Years later it was entered into a vintage race with none other than the renowned Phil Hill as pilot. Handling had been updatedlimproved by the respected restorer Jan Voboril, who mainly had stiffened the front shocks, softened the rear spring, and positively located the rear end sidewise ... and perhaps even mounted larger tires in the rear.

But Buicks were not done with Milliken, nor was Milliken done doing experimental engineering with Buick. Adapting the Dynaflow to a Bugatti had been under the auspices of "play" as Bill Milliken was active in the sport of road racing, both as car builder and driver. His next research and development project for Buick and General Motors came as part of his employment as head of the Cornell University Aeronautical Laboratory at the time GM instituted a research contract that began in 1952, and would subsequently run through 1963.

The first project Milliken labels Equations of Motion and involved specially instrumenting a 1953 Buick in order to run "a comprehensive test program that involved steady turning maneuvers and the transient maneuvers that occur on turn entry and recovery ... Correctly sorting out the inertia coupling terms of this system (enabled us) to identify the modes of motion and fully explain steady-state and transient responses of the ... automobile for the first time."

The next project involved developing comprehensive data on the pneumatic tire. Obtaining data required developing a tire testing machine that actually pioneered flat-surface testing and led to additional research contracts from the tire manufacturers.

Although the concept of power steering had been around since the 1903 Columbia Electric Motor Truck came equipped with a separate electric motor to assist steering, it wasn"t a generally prominent feature until the 1951 Chryslers and 1952 Buicks appeared in showrooms. Developing the "steering feel" became a major program for Cornell and specifically Bill Milliken"s team for its client, General Motors Research Laboratory Division. The first Artificial Feel and Force Control Car was a 1954 Buick and since this became an on-going long-running project, a second car, a 1956 Buick, was modified to incorporate and test findings from the development of the earlier car.

In 1963 Milliken was promoted to the directorship of the Lab One portion of Cornell"s renamed Transportation Research Division. This would prove to occupy him with a variety of creative research projects for General Motors, Goodyear, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) and others for another decade plus - until mandatory retirement at age 65 in 1976. "But," writes Milliken, "I had no intention of retiring."

Milliken"s career had begun with a fascination with flight that translated to building his first two gliders in 1924 at age 13. As a high school senior he embarked upon the design and construction of a parasol monoplane. Those adventures are recounted in the chapter titled Designed, Built, Flew and Crashed. In spite of the implication in the chapter title, the airplane was not a frivolous effort, and testifying to that is that today it is restored and on display in Maine"s Owl"s Head Transportation Museum.

Milliken went on to obtain his engineering degree and accumulating hours as a pilot. Subsequent to graduating he worked with Chance Vought. In 1939 Boeing offered him a position where, among other things, he would be involved in early work developing pressurized aircraft. As Milliken wrote, "Flying jet transports at 30,000-40,000 feet now is so commonplace that it is difficult to describe the sensation of reaching these altitudes on oxygen alone, after months of trying, or later oil a single flight."

But I can guarantee you that it all makes for fascinating reading.

Commencing his non-retirement, Bill Milliken formed his own company, Milliken Research Associates, with his two sons. MRA"s client list and accomplishments reflect its founder"s incessant curiosity.

Beverly Rae Kimes phrases it exquisitely in her closing Editor"s Note: "Among the greatest pleasures of my career as an automobile historian has been collaborating on their personal stories with the people who have made that history. I can say unequivocally that never have I enjoyed being anyone more than Bill Milliken. Beginning with the adolescent who was equal parts Peter Pan and Dennis the Menace, and who really hasn"t changed much more than eight decades later, Bill"s life has been one of unrelenting adventure, together with risk and innovation.

"There was a lot to learn editing the estimable Mr. Milliken. I"m better at math now, can fathom a bit of physics, and understand vehicle dynamics. Bill gave me my first chance to fly an airplane, I wind tunneled, experienced tail stall, and tested all sorts of marvelous aircraft. I drove a four-wheel-drive Miller, a Dynaflow Bug, and spun out dramatically at a certain corner in Watkins Glen. Nowadays I find camber really sexy. It"s been a super ride."

And you"ll think so too when you sit down to read Bill Milliken"s Equations of Motion.

Review of Equations of Motion from The Buick Bugle - February, 2008

![[B] Bentley Publishers](http://assets1.bentleypublishers.com/images/bentley-logos/bp-banner-234x60-bookblue.jpg)