|

Zora Arkus-Duntov: The Legend Behind Corvette

by Jerry Burton

Price: $49.95

|

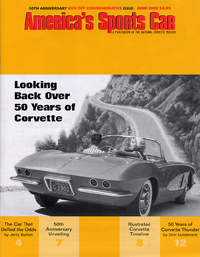

America’s Sports Car – June 2002

Corvette’s longevity in the fragile world of automotive nameplates was anything but a sure thing. But Zora Arkus-Duntov and his successors stood tall, ensuring not only the car’s survival, but also its proud legacy that has withstood 50 years.

The Car that Defied the Odds by Jerry Burton

Perhaps the best way to appreciate the significance of a 50-year anniversary for the Corvette is to understand how close the car came to not making its 5th anniversary. The Corvette got off to a rocky start in 1953 and 1954. Corvette production in 1954 (3,654 cars) was more than ten times the number of cars built in 1953, yet many of those units were languishing on dealer lots. Whatever novelty existed for the Corvette in 1953 had already worn off. Serious sports car enthusiasts just couldn’t get worked up about a car with a two-speed automatic and a six -cylinder engine. And even a though a V-8 engine was offered in 1955, demand was so low that only 700 total Corvettes were built that year.

GM was abuzz with rumors that the Corvette was dead.

But several things happened to turn things around. One was that Chevrolet’s archrival, the Ford Motor Company, introduced ins own Corvette competitor, the Thunderbird, in 1955 as a 1956 model.

Secondly, Zora Arkus-Duntov, who had come onto the scene in 1953 as an assistant staff engineer, was starting to make some noise.

To Zora, who held no real sway on Corvette matters at that point, the fledgling sports car’s problems spelled opportunity. GM at that time had few people who truly understood sports cars and Zora saw the existing vacuum as a way to position himself as the “go-to” guy on sports car matters. He started by taking advantage of speaking opportunities on the Society for Automotive Engineers banquet circuit. Using his perspectives gained from racing in Europe, Duntov’s typical theme was what makes a sports car and what motivates sports car buyers. In making these speeches, Zora could underline his voice of authority on the subject in the hope of gaining a greater engineering influence over the Corvette.

Zora had a chance to play a more pivotal role on Corvette matters after an anonymous GM executive buttonholed him in Fall 1954 and announced with glee that the Corvette was “finished” and no more would be built. Outraged, Zora wrote a memo to Cole and Olley dated October 15, 1954 to try to save the car. “By the looks of it, Corvette was on its way out,” Zora wrote.

Zora suggested that the Corvette failed thus far because it did not meet GM standards of product. It did not have value for the money.

“If the value of a car consists practical values and emotional appeal,” wrote Zora, “the sports car has very little of the first, and consequently has to have an exaggerated amount of the second.” It was in the performance area where the Corvette fell short, suggested Zora, especially with the six-cylinder engine where it performed no better than a medium-priced family car. Zora, of course, firmly believed that the more the Corvette performed like a racecar, the more popular it would be as a street cat. It was a belief that would fuel many disagreements in the coming years at GM.

Duntov cited the debut of the Thunderbird, a car of the same class as the Corvette and warned that if Ford is successful where GM failed, it may be a major embarrassment to GM. “If it dies, it is an admission of failure. Failure of aggressive thinking in the eyes of the organization, failure to develop a salable product in the eyes of the outside world.”

Zora acknowledged that a car line like the Corvette with a sales volume of 3,000 to 10,000 units was bound to be a hindering stepchild in an organization that thinks in terms of 1.5-million units. He understood that there was a larger opportunity here-that the Corvette could have a role in lifting awareness and respect for Chevrolet around the world. “The value must be gauged by effects it may have on overall picture,” insisted Zora. This was an important realization, for Zora had pinpointed the foundations on which the Corvette would enjoy its future success-as a halo vehicle for other Chevrolet products.

Given this much more important role, he then made the case for what he was really seeking all along-a team within the organization that would eat and sleep Corvette. “I am convinced,” wrote Duntov, “that a group with a concentrated objective will not only stand a chance to achieve the desired result, but devise ways and means to make the operation profitable in a direct business sense.”

Duntov didn’t get his dedicated engineering team, at least not right away, but may have saved the car with his memo, while establishing himself as the authority on Corvette matters. Engineering decisions were still the prerogative of Chevrolet chief engineer, Ed Cole, who was succeeded by Harry Barr in 1956. But Duntov attracted the bulk of the Corvette assignments such as application of the small block V-8 to the Corvette in 1955, the subsequent improvements to that engine and the ongoing development of the fuel injection. More importantly, Zora was developing a growing atmosphere of support for his ideas among senior managers.

Zora took his new status and soon used it to provide some true performance credentials to go along with its great sports car looks. He would go on to develop many technologies that debuted on the Corvette and have since become household words in the auto business. These included the Duntov cam, based on the cam profile of his Ardun overhead valve conversions for Ford flathead V8s back in the 1940s.

He used it to break the 150-mph mark for Corvette on the sands of Daytona Beach in January 1956. He was also helping develop fuel injection at the same time, working with a team from Rochester Products Division led by John Dolza. Fuel injection would debut on the 1957 Corvette, producing one horsepower per square inch. The first fuel injection systems were crude, but they paved the way for the widespread application of the technology today.

Zora later developed Corvette’s first independent rear suspension with the transverse leaf spring in 1963. Two years later, in 1965, he introduced disc brakes and Corvette’s first big block engine-the 396.

Zora also created a racing pedigree for the Corvette, starting in 1956 with Corvette’s first factory effort and later with the purpose-built Corvette SS racer, which made its debut and swan song in the same race-at Sebring in 1957. The SS was a victim of GM’s adherence to the Automotive Manufacturer’s Association’s ban on racing, a policy that would thwart Zora’s later efforts to race Corvettes like the Grand Sports in the early to mid 1960s. But Zora maneuvered around corporate dictates as best he could and managed to develop the Corvette a formidable racecar, even though it was customers who were doing most of the racing.

Duntov saw a rear, mid-engined Corvette as the next logical direction for improving the performance of the Corvette, despites the disadvantages of the design in terms of creature comforts, noise and rear visibility. But Zora at heart wanted to build racecars and felt that the manufacturer who came the closest to building a well-balanced racecar on the street would own the market.

Zora was never successful in this quest, despite commissioning a number of mid-engined prototypes including a dazzling machine called the Aerovette that made the rounds of auto shows and press previews. But Duntov was successful in creating a buzz. The mid-engine speculation, along with the ongoing technical developments that appeared in production Corvettes and the steadily growing racing pedigree, all helped propel the Corvette to profitability, which helped it survive and thrive within the world of GM where volume and profits were king.

Zora retired at age 65 in 1975 and his place was taken by Dave McLellan, who suddenly faced the mission of how to restore the Corvette’s performance credentials after the car was emasculated due to emissions controls and concerns over gas mileage in the early 1970’s. In time, McLellan not only brought the Corvette back to life performance wise, but he went on to set new performance plateaus for the car.

His fourth-generation Corvette and its derivations, which included the “King of the Hill” ZR-a with over 400 hp, provided supercar performance while still beating gas guzzler regulations. McLellan also defined the construction and configuration of the fifth-generation Corvette during a period during the early 1990s when the Corvette’s future wasn’t a sure thing.

Dave McLellan retired in 1992 and was replaced by Dave Hill of the Cadillac division. Hill presided over the final details and launch of the fifth-generation Corvette in 1997-heralded by critics as the best Corvette ever and a machine that can truly stand on its own merits against any automobile in the world. He also supported the engineering efforts to make Corvette a racecar capable of winning international races, which it did at the 2001 Rolex 24 at Daytona. Months later, Corvette swept its class at Le Mans. Hill is no hard at work on the next generation Corvette.

Meanwhile, we begin a yearlong celebration of 50 years of Corvette this June at NCM. The Corvette-the car that could have easily slid into oblivion during its formative years-now stands proudly as the longest running nameplate in the Chevy car family. For indeed, it is the legacy of Corvette defined by Duntov, McLellan and Hill-and their respective teams from engineering and GM Design Staff-that makes all Chevys shine a little brighter and all Corvette owners stand a little taller.

Jerry Burton is the editorial director of Corvette Quarterly magazine and author of the new book Zora: The Legend Behind Corvette by Bentley publishers.

See the review

![[B] Bentley Publishers](http://assets1.bentleypublishers.com/images/bentley-logos/bp-banner-234x60-bookblue.jpg)