Winding Road columns by Karl Ludvigsen

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Return to Karl Ludvigsen main page

Motor Sport's Mister Inside

Behind the gregarious character of Bernard Cahier was a generosity that found him productively involved in the careers of teams and drivers. Bernard also put his Leica and Pentax to the best possible use.

When I was handling public relations for GM Styling Staff in the early 1960s Bernard Cahier posed certain problems. Bernard's friendship with design chief Bill Mitchell was such that when he visited Detroit the genial Frenchman would stay with Bill, who would bring a swathe of his latest prototypes to his home in Bloomfield Hills for Cahier to drive and photograph. This was a PR man's nightmare-a journalist completely out of his control!

This however was an example of the kind of intimacy that Bernard Cahier enjoyed with the luminaries of the world motor industry. He was on similarly chummy terms with BMC's Alec Issigonis, Dante Giacosa at Fiat, Porsche's Huschke von Hanstein and Rudolf Uhlenhaut at Mercedes-Benz. Like not a few motoring journalists Bernard wasn't shy about accepting their favors in the form of room, board and entertainment. He wasn't conspicuously generous in return. When I managed to grab the check after a lunch at Le Chanteclair he was visibly miffed. "I don't often offer to do that," Bernard admitted.

You could only relax and enjoy the friendship of Bernard Cahier and his vivacious blonde wife Joan, an American whom he met and married while they were both studying at UCLA. As I found in 1958, it was an agreeable ritual for drivers and team owners to go down the coast to their home near Nice for an enjoyable reception in the run-up to the Monaco Grand Prix. Never at a loss for a joke or amusing aside, Bernard was the ultimate in amiability as host.

How did this Frenchman with the wide-set eyes and broad grin become such a star of the motoring world? His entrťe was his role as a photojournalist for L'Action Automobile in France and Road & Track in America. He began working for the French magazine in 1952, his first photo shoot the Italian Grand Prix.

Cahier created his American connections in the late 1940s after UCLA. He took a job as a salesman at Hollywood's International Motors, run by Roger Barlow. A fellow salesman was Phil Hill while Richie Ginther was in the service department. John and Elaine Bond of Road & Track couldn't fail to be impressed by Bernard's enthusiasm for the burgeoning world of sports cars.

In June of 1952 Bernard and Joan settled in France, where Cahier had impeccable forebears. His father was in the French military, rising to the rank of general, while his sister was the wife of the brother of Francois Miterrand, destined to be France's president. Initially from a base in Paris Bernard began fashioning his motor-sports credentials.

Soon photos and reports from Cahier began to appear in Road & Track. By 1954 he was listed as a contributor and in mid-1955 he was officially anointed the magazine's European Representative. At the end of that year R&T editor John R. Bond made his first trip to Europe. Arriving in Paris, Bond related, "we were met by our European representative and correspondent Bernard Cahier. A wild ride from Orly field to the heart of Paris in Bernard's trusty 2CV and a taxi left us all a but shaken, but still in one piece." Joan and Bernard made sure Bond and his party enjoyed the best of Paris's fabled night life.

Cahier's contributions were upbeat and uncritical, which helped his currying of favor among the world's motoring elite. They could be sure he would keep their confidences. Nor was he terribly technical. But he had unparalleled access that gave him first crack at new models and even new companies. In 1961 he took these talents to Petersen Publishing, which was rolling out Sports Car Graphic as a new monthly to compete with R&T and with Car and Driver, which I was editing at the time.

Waspish chronicler of the Grand Prix scene Louis Stanley called Cahier "an irrepressible scribe," saying that "for years he has darted about with a foot in every pit. He represents journalism by the odd expedient of not taking it too seriously. His style is sharp and colloquial-at times he reminds me of the brilliant talker who impresses the hell out of you at a cocktail party but who, when he turns to go home, seems vaguely lost. In Bernard's case it hardly applies for there is always his Joan, a patient wife, who takes over. They make a delightful team."

Though his road tests could be anodyne, Bernard Cahier was no slouch behind the wheel. In 1956 he joined a squad of Renault Dauphines entered in the Mille Miglia alongside such aces as Grand Prix racers Louis Rosier, Paul FrŤre and Maurice Trintignant. Bernard and feminine co-driver NadŤge Ferrier were tenth in class and 154th overall in this classic race throughout northern Italy.

Another outing for Cahier late in 1956 was as a member of a crew of journalists recruited to drive a Bertone-bodied Abarth-Fiat at Monza to tackle records in the 750 cc class. Joining such well-known writer-drivers as Paul FrŤre, Gordon Wilkins and Johnny Lurani, Bernard more than held up his legs of the assignment, including demanding night-time stints during the successful run.

By far Bernard Cahier's finest motor-sports achievement was his drive in the 1967 Targa Florio, 447 miles through the jagged hills and chasms of northern Sicily. Driving a works-prepared 911S Porsche he placed seventh overall and won the class for 2.0-liter GT cars. Sensationally his co-driver was fellow Frenchman Jean-Claude Killy, triple-gold-medal winner in the Winter Olympics. Together they gave the then-new 911S its first important success.

Cahier was also a wheeler-dealer in motor sports behind the scenes. When Californian Dan Gurney first visited Europe in 1958 Bernard arranged the loan of a Renault Dauphine in which Dan and 1958 Indy winner Troy Ruttman drove from race to race and practiced on the NŁrburgring. There Gurney competed in a 1.5-liter Osca, a ride which Cahier negotiated from Guglielmo "Mimo" Dei's Scuderia Centro Sud in Modena. The loan of a fatigued 250 F Maserati by Dei to Ruttman was less of a success.

Right up Bernard Cahier's alley was the plan of director John Frankenheimer to film a movie about Formula 1 racing. Making himself indispensable to Frankenheimer, Cahier became a consultant to production of Grand Prix. He even had a bit part in character as a journalist. Louis Stanley recalled a filming in which Bernard was to enter a room with Juan Fangio and film star Yves Montand: "The first shot halted when the trio jammed in the doorway; the next shot ended with a mini-struggle to get through, and finally Fangio and Montand emerged with Cahier bringing up the rear."

This was heady stuff for Cahier, who was born in Marseilles in 1927. He saw his first Grand Prix at nearby Miramas at the tender age of five. As a teenager he aided the wartime resistance in Brittany and toward the end of the war joined an engineering arm of General Leclerc's Second Armored Division, attached to George Patton's Third Army. After war's end he helped with vital mine clearing.

The post-war era brought a year in the French colony of Cameroon and then Bernard's California phase and his fateful meeting with Joan Updike at UCLA. The couple often wintered with her family at Long Beach in future years. Their son Paul-Henri carried on his father's tradition, specializing in motor-racing photography and building up their formidable archive accessible at www.f1-photo.com.

With other aspects of top-line racing getting more professional, Cahier saw the need to provide clear recognition for people who were seriously covering motor sports. In 1968 he was one of the founders of the International Racing Press Association. Its members were granted press facilities by the FIA and Bernie Ecclestone's growing FOCA. In the IRPA's early days Bernard was its president.

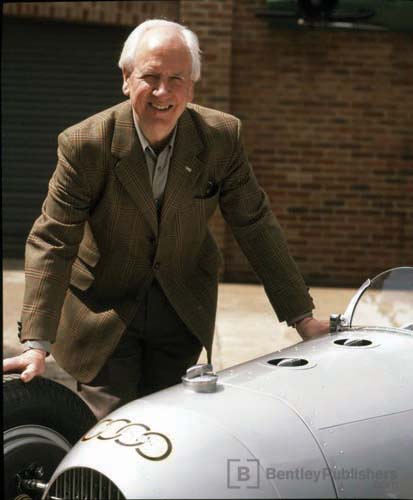

The tire wars of the 1970s brought a new role for Cahier as a roving public-relations ambassador for Goodyear, an assignment tailor-made for his gregarious nature and love of a good cigar. He continued in this role to 1983. Thereafter, however, no race or motor show was complete without an appearance by Bernard, usually in tweeds with a new confidence or two to impart.

When I wrote my book about the career of Jackie Stewart (Haynes 1998), Bernard was very helpful with photos. I dedicated the book to Cahier, calling him "Friend, colleague and fine photographer whose many and valued contributions to motor sports over 50 years will only be appreciated when he writes a book of his own." He subsequently did just that, titling it F-Stops, Pit Stops, Laughter & Tears.

I'm very glad that Bernard got around to that, because he left us on July 10 of this year at the age of 81. You often hear people bemoaning the lack of big personalities among today's racing drivers. Well, the same applies to journalists. They've stopped making the likes of Bernard Cahier.

- Karl Ludvigsen

Challengers' Chances

Exploiting the auto industry's new paradigm that demands low fuel consumption and CO2 reduction, ambitious would-be entrants are crowding in to challenge the established companies. Experience tells us they'll face some daunting obstacles.

Looking back, I was surprised to be reminded that I'd played a minuscule role in the advancement of the hybrid car. I was friendly with a GM engineer, Donald Friedman, who'd left the General to set up Minicars, Inc. in 1968. As the name suggested Don's aim was to fill a gap in the transport infrastructure with small cars that would be chiefly urban, offering high serviceability and utility with low emissions.

In addition to an LPG-powered version, Friedman and his colleagues experimented with a hybrid drive train. When Don gave a speech about his activities in 1969 my PR company, Mobility Systems, issued a news release describing his experimental "gasoline-electric hybrid engine" and showing his breadboard set-up for testing. Minicars envisioned a test launch of 100 cars in Philadelphia in 1970 as a springboard to production of 2,500 cars a year.

I thought of Minicars and some similar past efforts in the context of what I see today as a remarkable number of new initiatives to break into the auto industry. California has some of the highest-profile efforts in Tesla's electric roadster and Fisker Automotive's Karma hybrid sports sedan. Hot on their heels is a joint venture with Norway's Think! that aims to produce up to 50,000 electric cars a year in Menlo Park, while Carlsbad's Aptera Motors is making its radically streamlined Typ-1 in both electric and hybrid versions.

Tata's low-cost Nano isn't the only new challenger from India. Reva's G-Wiz electric city car is all the rage in London. New Italian entrants are the Maranello4, Elettrica and Micro-Vett Ydea urban electric cars, while French companies looking for electric-car-buying customers are Aixam-Mega and the producer of the Microcar MC2, converted in Toronto to the electric ZENN for sale in America.

In Britain Stevens Vehicles is gearing up to produce its Zecar autos and vans, both electric, while the Lightning Car Company's Lightning GTS plans to upstage the Tesla with much more performance at a much higher price. Another British newcomer, Connaught, sees a hybrid drive as an important adjunct of its stylish V-10-powered sports car. Another hybrid sports car is being developed in Belgium by Imperia, reviving a respected marque.

This is a pretty impressive roster of newcomers to the motor industry. From time to time we see people and companies with ideas about becoming serious car makers, but this is more a tsunami than a tidal wave. And it's obvious that they all have something in common: the use of new technology, either electric or hybrid or both.

This is significant. When car technologies are static, changing little from year to year, it's difficult for an attacker to find a vulnerable niche. In this environment the established makers refine their designs and reduce their costs, making them even tougher competitors. But when there's a paradigm shift, either generated internally from new technologies or imposed externally by new market requirements, the qualified challenger perceives a chance to break into the auto industry.

We have just such a paradigm shift today. The high and rising cost of fuel and the imperative of reducing fuel consumption to cut down on CO2 emissions have combined to force significant changes in auto engineering. To be sure the established auto makers are struggling to adapt to the new realities, but they're perceived as the Bad Guys, the Neanderthals who try to resist change. This opens a terrific opportunity for newcomers who can wear the White Hats of earnest virtue.

We've had these opportunities before. My friend Friedman's Minicars was ahead of a curve that shot steeply skyward in the 1970s with the two Energy Crises. This brought many electric-car makers out of the woodwork. One of the first to hum to prominence was Sebring Vanguard, whose CitiCar enjoyed a wave of popularity as did its successor, the Comuta-Car. For the U.S. Postal Service a fleet of 350 Jeep-like electric delivery vehicles was produced by AM General, later famed as the Hummer's maker.

Of all the potential new entrants to the industry in those days, the big producers of electrical equipment seemed the most likely. They had to money to invest, the needed technologies at their fingertips and manufacturing operations that could be adapted to produce automobiles. Here was an unprecedented opportunity to penetrate a lucrative industry, to win back the electric's advantage at the turn of the century. In 1900 American car production numbered 1,575 electrics against only 936 gasoline-powered cars. Of the 8,000 motor vehicles then in use in the United States, fully 38 percent were battery-driven.

Top of the list was General Electric. As a maker of electric cars their pedigree was impeccable. And they had a production prototype. In 1978 GE unveiled its Centennial Electric to celebrate its first 100 years. The slope-nosed two-door hatchback was designed and built for GE by Michigan's Triad Services. It was led by the creative Mike Pocobello, a former Chaparral Cars engineer. Claimed for the Centennial Electric's lead-acid batteries were a top speed of 60 mph and range of 75 miles at a constant 40 mph-not bad numbers 30 years later.

On the strength of this effort GE teamed up with Chrysler to produce two electric prototypes under a $6 million Department of Energy contract. The result was a sophisticated four-passenger subcompact whose batteries were housed in a central tunnel like those of the Centennial Electric. Publicly GE disavowed any interest in entering the auto industry, saying that its only aim was to sell drive trains and controllers to the established cars makers.

Another big supplier of electrical equipment, Westinghouse, acknowledged no such constraints. At its electric vehicles operation in Redlands, California it had been making a range of three- and four-wheeled electrics for off-highway carriage of people and cargo. In 1967 it built on this expertise with production of the Markette, a shoebox-shaped two-seater that was initially priced just under $2,000. Westinghouse planned output of 500 in the first year and as many as 50,000 annually thereafter.

Reality bit hard. "It was a dog," said a Ford researcher of the Westinghouse runabout. With each Markette costing Redlands up to $2,700 to produce, the price soon rose to $2,800. Production was halted after 65 were made. The company blamed the new safety standards. "We didn't know about the Safety Act when we went into that business," admitted a Westinghouse official. "We decided to back away from it until we could get better batteries to build a higher-performance car." That day has been long in coming.

Speaking of batteries, their makers invested in electric-car prototypes in the 1970s. A beauty, the Endura, was built for battery maker Globe-Union. ESB Inc., maker of Exide and Willard batteries, commissioned advanced electric vehicles from Chicago racing-car builder Bob McKee. Their two ultra-light Sundancers were successfully tested for more than 10,000 miles.

For obvious reasons the Copper Development Association also got into the act. Its swoopy Electric Town Car, another product of Triad Services, claimed a range of 103 miles at a 40-mph cruise and a 73-mile action scope in city driving, aided by regenerative braking. But this was clearly a promotional effort by an industry association that aimed to raise the profile of its material-so much so that its electric prototype had copper-alloy brake drums.

Last time around, then, the bigger battalions of the electrical industry failed to make significant headway in the motor industry. Thirty to forty years later, however, newcomers might have a better opportunity. Car buyers are less wedded to traditional brands, thus more willing to take a chance on a new marque that offers a special appeal to their pocketbook and/or social and environmental consciousness.

On the other hand, the obstacles that were present then would still hamper newcomers today. One is perhaps less significant. This is the extreme reluctance of suppliers to the indigenous industry to be seen to be competing with their customers. That's why battery makers, for example, always stressed that their concept cars were just that, not potential rivals to the auto makers. In today's more free-wheeling global industry, with joint venturing running rampant, this is less of a constraint.

Another obstacle still looms. This is the need for a sales and service network. Their distribution systems are in fact the crown jewels of the auto companies, their barriers to entry by rivals. Where car companies develop good networks and tie them closely to their brands, they can and do make it difficult for pretenders to make headway. Though the force of this obstruction varies considerably from nation to nation, according to their traditions and regulations, it's a daunting barrier to entry into the industry, one that many bright-eyed entrepreneurs tend to underestimate.

On balance I think the new generation of would-be entrants has a lot going for it. They have a much wider choice of producing nations, thanks to the rise and rise of India, Korea, China and others. Engineering expertise is available from the Porsches and Lotuses of this world. And the trend in legislation has given dealers more freedom to take on new brands. All in all, then, the outlook is bright. Although too late for Minicars, the new industry paradigm has arrived in good time for Fisken and Tesla, to name only two.

http://www.lightningcarcompany.co.uk

- Karl Ludvigsen

Four-Leaf Clover Lucky this Time?

Because Alfa Romeos are so attractive they've had more than their far share of exposure in Winding Road for cars that aren't on sale in North America. Fiat may finally be getting its exotic daughter in shape for a fresh attack on the New World.

Fiat's takeover of Alfa Romeo in 1989 was a culture clash of the first magnitude. Imagine Toyota acquiring Nissan? GM buying Ford? Daimler scooping up BMW? Here were two great rivals in their home market, Alfa assuredly the minor player but very proud of his history and the prestige of its brand-perhaps too proud.

The two Italian companies had coexisted quasi-amicably until 1972, when Alfa Romeo aimed an Exocet into Fiat territory with its cheeky Alfasud small car, made in a former aircraft-engine factory near Naples that was rebuilt with taxpayers' money by government-owned Alfa. Here, thought Fiat-not without reason-was unfair competition on its home ground. Though bedeviled by strikes and absenteeism, the Naples plant produced an attractive car conceived by Austrian Rudolf Hruska that was a lively domestic alternative to Fiats and an export success until rust ruined its reputation..

Fiat has struggled in trying to manage its Alfa acquisition. After the takeover it created a new company called Alfa-Lancia, forcibly marrying the Milan company with its long-time Turin rival, which Fiat had rescued from the breaker's yard in October 1969. Famously there is no love lost between the cities of Turin and Milan; each has contempt for the other. And in naming the joint company Alfa-Lancia the proud Alfa Romeo name was mortifyingly truncated (much like the erasing of Benz from DaimlerChrysler).. When I braced senior Fiat people on this point they feigned mystification. They were the conquerors; they could do as they liked.

Fiat Auto's dynamic managing director, Vittorio Ghidella, was named chairman of Alfa-Lancia. In an interview he was scathing about Fiat's new acquisition, briefing a reporter that it was 'in serious trouble because of the strategic error of having attempted to enter the small-car market with its humble Alfasud,' which 'went against the image of power associated with Alfas for more than half a century. Alfa always sold well because of its exceptional performance and aggressive line until mistakes were made in recent years.' Ghidella tried to engineer some cost-saving commonality between Alfa Romeo and Lancia, but only two years later he was out of the Fiat Group after a bitter internal clash over its allocation of resources.

Missing the jet thrust of Ghidella, Alfa Romeo declined into the doldrums. Just short of 200,000 in Fiat's first year, 1987, production rose initially to 220-230,000 through 1990. Then it collapsed to half that level in 1993, 1994 and 1996. New models based on Fiat platforms arrived, but with excruciating slowness. Only with the launch of the gorgeous 156 in 1997 did Alfa sales start to recover, with more than 200,000 made from 1999 through 2001. In 2002, however, output declined to 187,437 Alfas. Production in 2006 fell to 157,775 and in 2007 was some 6,000 less still.

Most mortifying of all has been the negligible market success of Alfa Romeo's prestige flagship, the 166. Its predecessor, the Enrico Fumia-styled 164, made a valiant effort to establish a place for Alfa in the executive-car market, selling a quarter-million over seven years, a decent annual average of 35,000. In contrast the 166 has muddled along at annual volumes of 8,000 that Autocar called 'pathetic'.

I discussed this and the parallel problems of Lancia with a Roman friend who is knowledgeable in the field of auto design. 'I think the reason that the Italians don't do well with luxury cars is that they lack the necessary culture,' he said. Italy has a flourishing culture in small cars and sports cars, segments in which it's among the world's best. But luxury cars? Italians just don't believe in them. They're heavily dutiable and an all-too-visible sign of wealth that attracts the tax man. Italy's finest post-war effort in the luxury-car field, Lancia's Flaminia, struggled vainly against these handicaps. Italy should be able to make outstanding executive cars. But her designers and engineers lack a heartfelt commitment to this class of car. That they don't like the Berlusconi-class people who drive them is all too obvious.

Another handicap for Alfa Romeo is the brand's insularity. All but a handful of its cars are sold in Europe; the rest of the world doesn't exist. Even at that the picture in Europe is not reassuring; Alfa Romeo's European share is sub-one-percent. A key market, Germany, has seen a steady decline from 2001's 25,700 units to 19,000 in 2002, 15,000 in 2003 and less than 12,000 in 2007. Although 89 percent of German Alfa owners say "I like my brand", that figure is down from the previous 93 percent. Even more worrying is a drop from 24 percent to only 18 percent of Germany's car enthusiasts who say of Alfa Romeo "I like the brand".

The story of Alfa Romeo in North America is no more pretty. A friend was an Alfa dealer in Cleveland; in the 1960s he went two years without new cars and Milan didn't seem to think that was anything out of the ordinary. Alfa relied on the fact that it had a core of dealers in America who were so dedicated to the marque that they would put up with anything, including indifferent quality and elusive parts supplies. Those days are long gone, of course, now that dealers have been badly spoiled by the Japanese. And the attitude of Alfa's men in America didn't help. "What's the matter with these Americans?" one grumbled to me in frustration. "Don't they know this is an Alfa Romeo?"

I breathed a sigh of relief when I heard that the original plan to return Alfa Romeo to America in 2003 was postponed. In the wake of Fiat's "strategic alliance" with General Motors in 2000 the first signs were that Alfa would be back in jig time but with a minimal model range, a sure-fire recipe for disaster. It was thought then that Alfas would piggy-back on the GM dealer network, a concept that brought back memories of the ill-fated partnership between Chrysler and Alfa Romeo in the late 1980s. This was a vestige of the failed talks between Chrysler and Fiat Auto that had hoped to achieve an alliance. Against goals of selling up to 30,000 cars a year, the effort struggled to move 8,000. Alfa carried on alone and sold 414 cars in its final year in the States, 1995.

Next the plan was to return to America in 2007 with a full line of the new cars that have been launched in Europe in 2005 and 2006, the 159, Brera, Spider and GT. The goal then was said to be annual sales in the 50-60,000 bracket, which sounded awfully high. Nor was the idea convincing of selling Alfas through Cadillac, Saab and Saturn dealers. Saab outlets might have a fighting chance, but otherwise these aren't dealerships that would attract people who'd consider an Alfa Romeo. Its dealers should be stand-alone outlets backed by people who understand the sporty-car market. They're out there, but whether they want to sign on for another roller-coaster ride with Alfa Romeo remains to be seen.

Since the bad old days of Alfa-Lancia, Fiat has made some effort to rediscover the brand's soul. Alfa Romeo is a separate business unit with some autonomy. But its top executive's chair has been something of an ejection seat. First to take it in 2002 was manufacturing engineer Daniele Bandiera. He was followed by Antonio Baravalle, who left Fiat in 2007. Instead of a direct replacement his seat was filled by Fiat wonder boy Luca De Meo, who's also in charge of all the Fiat Group's marketing activities. De Meo jumped to prominence after joining Fiat in 2002 to head Lancia's marketing.

Luca De Meo is one of the new crew recruited and promoted by Fiat CEO Sergio Marchionne. Joining Fiat's board in 2003, barrister and accountant Marchionne was appointed its CEO on the first of June, 2004. With neither fear nor favor he swept out most of the old guard and appointed new young talents to key positions, among them De Meo. The bad news is that this meant the departure of many long-serving experts. The good news is that this meant the departure of many long-serving experts, among them the dyed-in-the-wool Alfa Romeo people who, like my friend above, just couldn't understand why people weren't buying Alfas.

Now the expectation is that Alfas will return to America in late 2009 as 2010 models, just in time to celebrate the centennial of the company, which traces its origins to 1910. Much is being made of the role of the exciting 8C Competizione as a harbinger of the range, with its Spider sister as well. More important will be the merit of the affordable models in the range. Here there's reason for concern. They're based on the "premium Epsilon" architecture developed during the GM-Fiat alliance, a platform that GM itself abandoned in 2003 for reasons of "weight", according to GM product czar Bob Lutz.

The effect of this is all too evident. Comparing the Brera with its rivals in Number 16, Winding Road found a "glaring difference in dynamics" owed to "the Brera's weight. We drove all four cars at their true fighting weights onto a public scale and the Brera 3.2 Q4 at 3990 pounds weighs nearly 730 pounds more than its nearest competitor, the TT 3.2 Quattro at 3263 pounds! Even though we knew the Italian was heavier ahead of time, this mondo weight difference was a shock and it explains almost everything about how we felt toward the Brera." Nor were the car's other attributes up to snuff.

That's why it's good news that new people are on the Alfa Romeo case. They'll be less dependent on the fading glories of the brand and more likely to be aware of the product shortcomings versus rivals that urgently need attention. One man who'll be dealing with that is Frank Stephenson, the stylist credited with both the New Mini and Fiat's retro-styled 500. He took over the Alfa Romeo studios at Arese near Milan in June of 2007. Former chief designer Wolfgang Egger did the 8C Competizione and the new MiTo small car unveiled on our May 2008 issue.

In its racing heyday the emblem of Alfa Corse, the company's in-house racing team, was a four-leaf clover. This brought Alfa Romeo a lot of luck, including the first two Formula 1 world championships of 1950 and '51. Alfa will need a lot more luck when it tries to take another bite of the American cherry. Let's hope that it finds the right management, the right timing, the right dealers and the right cars, because a little affordable Italian sporty luxury could go a long way in the New World.

- Karl Ludvigsen

Those Cars of the Year

As "Car of the Year" awards proliferate we start wondering what they're all about. Our man who's been there, done that takes you behind the scenes.

I was party to a virtual meltdown of the world's first and best-known Car of the Year award - at least according to the suits at Petersen Publishing. The occasion was Motor Trend's 1972 award, when for the second year I was a member of its adjudicating panel cleverly dubbed CARS - Conference of Automotive Research Specialists.

I was in great company. On the panel were Phil Hill, who needs no introduction, and Bill Milliken, engineer extraordinare whom I wrote about in Winding Road Number ??. Also on board were ace car designer and Art Center course leader Strother MacMinn and Motor Trend Editor Eric Dahlquist. It had been Eric's idea to enhance the transparency and validity of MT's award by corralling the COTY finalists for a ride and drive by experts over the desert roads of Southern California. If the award had been tarnished by obviously commercial choices over the years - and it had - this could restore the balance.

We restored it, all right. From a field that included the Porsche 911S, Fiat 128 and Chevy Blazer we picked the CitroŽn SM. Doesn't ring a bell? That was CitroŽn's daring execution of a sporting two-plus-two powered by a V6 designed and built by Maserati, which CitroŽn then owned. Dahlquist and I argued for the merits of Fiat's 128, the authentic pioneer of a new wave of front-drive small cars, but Milliken's impassioned advocacy of the exotic SM carried the day.

Krakatoa's eruption was a mere whisper compared to the outraged ululations from Petersen's advertising honchos. CitroŽn! That pipsqueak of an importer! Not much chance of a wall-to-wall wave of ads from them. And that weirdo SM! What kind of car was that? At least Fiat would have pushed the boat out with some advertising, not to mention Chevrolet.

Completely lost on these worthies was that our impartial recognition of the merits of the offbeat SM restored great authority to a COTY award that had lost much of its credibility after it was given, for example, to the whole Pontiac lineup in both 1959 and 1965 and again to the Pontiac GTO in 1968.

MT's was the first-ever Car of the Year program. It traced its origins to the magazine's Engineering Achievement Award, given in 1952 to the 1951 Chryslers. By 1956 it had become established as an annual event in more or less its later format. Only in 1970 were imports given a look-in, with the disastrous 1972 consequences described above. Later imports were given their own award.

I was reminded of 1972's shenanigans by the latest European Car of the Year award. This has a tradition of its own. It began as an initiative of the gregarious Fred van der Vlugt, editor of the Dutch car magazine Autovisie. Having founded the weekly in 1955, he then decided to enhance its prestige by recruiting a panel of journalists to vote on a Car of the Year. The first was announced in 1963, the Rover 2000.

Soon after leaving GM to go freelance in 1967 I became the American correspondent of Autovisie and then a member of its judging panel. We chose the Fiat 128 in 1970, the CitroŽn GS in 1971 (the SM finished third) and Fiat's brilliant 127 in 1972. In the latter year, however, competition threatened from the powerful Stern in Germany, which started its own COTY award. Seeing clearly that competing awards would be good for neither publishers nor car makers, Fred van der Vlugt negotiated successfully to create a pan-European program in which participating publications in each country rotated the chairmanship.

The downside of this for yours truly was that non-Europeans were no longer needed as jury members. The upside, of course, was that the European COTY went from strength to strength as you can see at www.caroftheyear.org. Success in it was seen by European auto makers as important, as I recall from my time at Ford. We nabbed it with our first front-drive Escort in 1981, a big feather in our caps, while our Sierra was just edged into second by Audi's 100 in 1983.

Over the years Fiat Auto's cars have been adept at winning the European COTY. Cynics ascribe this to the hospitality lavished on jury members by the Italians, including magnificent gifts in the early days, but product merits of Fiats, Lancias and Alfa Romeos also played a role. In 2004 Fiat's Panda became the 11th Fiat Group car to win the European prize, beating the Volkswagen Golf and Mazda3 which were tied for second place.

For 2008 a Fiat was the choice again. Fifty-eight journalists from 22 countries elected the new Fiat 500 with 385 points against 325 for the Mazda2, in second, and new Ford Mondeo with 202 points in third place. Said the jury's president, Briton Ray Hutton, "The jury saw the new 500 less as a retro design and more as something new, smart and streetwise, with solid practical and technical virtues.

"The jury was not immune from its attractions," Hutton added. "Voting comments ranged from 'heart beats head', 'the most charming car of the decade' and 'it makes everyone smile' to 'simply irresistible'. The Fiat 500 sends out the message that inexpensive and economical small cars need not be dull, drab, boring and slow. They can be fun. Fun to look at, fun to drive, fun to travel in."

In another context, however, Hutton admitted that jury members had been kicking themselves for not anointing BMW's new Mini in 2002. The retro-styled Mini finished a meager fourth in that year's voting behind winner Peugeot 307, followed by Renault's Laguna and Fiat's Stilo. Their reasoning went that the Mini had been a roaring success while they, the COTY voters, had been short-sighted in not spotting this - as if the popularity of a new model, not its inherent excellence, were to be the new criterion for the European Car of the Year.

By choosing the retro-styled Fiat 500 - nothing but a new dress on the Panda that won in 2004 - the jurists scored a twofer. They made up for their failure to pick the Mini in 2002 and at one and the same time they named a car that was already a clear sales success. Their choice was also a tribute by the journalist jury to what seems to be a turnaround at Fiat Auto, as Ray Hutton said at the Berlin prizegiving:

"The new Fiat 500 is simply the right car at the right time. Its success - for it is already a great success, with demand far exceeding supply - confirms Fiat's turnaround as a car manufacturer. Five years ago the company was in trouble. Since then, the driving force of Sergio Marchionne and his mostly new management team - many of whom are here this evening - has re-thought the product line, halved development time, and put Fiat back where it belongs: as one of the world leaders in small, economical cars."

To my ears, at least, this has the unpleasant sound of sucking up to a much-liked auto maker, not at all the independent perspective that should behoove a jury that is assumed to choose an outstanding automobile on its particular merits. This, after all, must be the thinking behind a COTY: that such recognition should single out a car that people could and should buy with greater confidence than usual. To boot, it should be a car whose conception and engineering may point a constructive way forward.

I was heartened to learn that an international panel of 47 journalists has chosen the Mazda2 as 2008's World Car of the Year, as announced at New York's International Auto Show last March. Here's a car that deserves recognition. When it was launched in mid-2007 even the chauvinistic European press raved about its efficiency and ingenuity.

At a time when weight reduction is an industry obsession, the new Mazda2 is more than 200 pounds lighter than its predecessor. Thanks to this and its efficient engines it emits 15 percent less CO2 than the outgoing model. To boot the Mazda2 has cheeky looks, a delightful interior and hatchback practicality. In the WCOTY judging it came top of finalists that included the Audi R8 and Volvo C30.

In existence since 2004, the World Car of the Year looks like deserving more of our awareness. On the basis of the 2008 results, at least, it's by far the more serious of the many efforts to nominate a new car that merits your attention - and your money. Check it out at www.wcoty.com.

- Karl Ludvigsen

Destiny's Darling: the Diesel

I'd jumped into this Jaguar S-Type because I wanted to try one on the twists and turns of the Millbrook test track where the motor industry was showing its wares to writers. It was impressive. It was smooth with plenty of poke as you'd expect from a Jaguar. Handling was good too as was its interior trim - an impressive car. But I was surprised that its engine only revved to 4,000 or so. Didn't Jaguars have higher-speed engines?

The penny dropped when I returned the S-Type to Jaguar. This was its brand-new 2.7-liter twin-turbo V-6 diesel! It was phenomenally smooth and quiet with ample punch from its 207 horsepower and 320 lb-ft of torque. Developed in cooperation with diesel experts Peugeot, its engine had new-fangled common-rail oil injection and four valves per cylinder with twin overhead cams per bank. Now, powering the new Jaguar XF, it's rated by many experts as that car's best engine.

This is the state of the diesel art these days - so good that a so-called car expert can't tell the difference. And the Jaguar is just the tip of the iceberg of advanced diesel development. Consider for example BMW's 3.0-liter 535d six with its twin turbos in series. It pumps out 272 bhp in an engine that's happy to rev to 4,800 rpm. As low as 1,500 rpm it starts delivering 369 lb-ft of torque with its peak of 413 lb-ft reached at 2,000 rpm. That's oil-burning performance.

Although more modestly powered at 210 bhp at 3,800 rpm from 3.0 liters, the E320 V-6 diesel from Mercedes-Benz is evidence of a serious and persistent effort by that company to maintain its traditional position as a leader in diesel-powered passenger cars in North America. Using Bluetecģ exhaust-treatment technology this engine has just been certified for sale in all 50 states in the E320, ML320, R320 and GL320. Its torque of 400 lb-ft from 1,600 to 2,400 rpm gives this 24-valve Mercedes diesel ample shove while offering routinely better than 30 mpg and the potential of 40 on the highway in a full-sized vehicle.

GM is getting into the luxury-class diesel act with its announcement of a 2.9-liter single-turbo V-6 for the 2009 Cadillac CTS. A legacy of GM's short-lived liaison with Fiat, the engine is a project of GM Powertrain in Turin and will be built in Cento, Italy by diesel specialists VM Motori. Among its advanced bells and whistles the 24-valve aluminum-head V-6 has closed-loop combustion control, a variable-geometry turbo and piezo-technology injectors and pressure sensors. Its 250 bhp and 406 lb-ft will make this new GM diesel highly competitive.

If it's launched in the USA, this V-6 will be a change from GM's previous American-market passenger-car diesels. From 1978 to 1985 its Oldsmobile Division - renowned for its engine expertise - produced V-8 diesels in 5.7- and 4.3-liter formats and from 1982 to 1985 a 60-degree V-6 diesel of 4.3 liters. With pushrod overhead valves and Roosa-Master oil injection these engines, used widely across GM's range, looked like the high-fuel-mileage answer to the second Energy Crisis of the late 1970s.

Several factors militated against the long-term success of these engines, which in their first versions justly merited their reputation for unreliability. When the V-8 was launched in 1977 I interviewed the Lansing engineers about their handiwork. They took me through the engine's development, showing how they'd beefed up the base engine using casting patterns from an abandoned 7.5-liter V-8 and how they'd experimented with some 300 different designs and injection timings to evolve its combustion prechamber.

Their tests of the new engine were rigorous. Before a diesel went into an Olds, test engines racked up 45,000 hours of dynamometer durability runs. Prototype engines numbered 250, 29 of which went into a test fleet with cars in all parts of the States that had tallied almost a million miles when the diesel was introduced. But still they were rushed. When the diesel idea "caught on at the Corporation level," said an Olds engineer, "all of a sudden they were putting the heat on us to do it."

In haste some basics were overlooked. "GM Truck and Bus Group kept telling us there were many pitfalls that we didn't know about," the Olds engineer recalled, "and we missed one of the big ones. Because the diesel is always running at wide-open throttle, you have to test it over lots of hours. We were using a 200-hour test, so we thought we'd better move the diesel to 400. We later doubled that, but it was still inadequate. It took a 1,000-hour test to prove a diesel." By the time its V-6 was launched Oldsmobile had learned this lesson.

Then the engine's manufacturing was short-changed. Those in charge of the purse strings thought the diesel might be a passing fad, so they approved only the minimum budget needed to set up a production line. When the engines were allocated to other GM divisions the completely new service training that was needed by all dealerships was rushed as well, the result being that mechanics in the field were poorly equipped to cope with problems as they arose.

And they arose. Water in the fuel caused rusting in injector pumps. Head gaskets blew and heads warped. Head bolts, rockers and pushrods failed. Starter motors broke. Failure to change oil at the unusually and unfamiliarly short interval of 3,000 miles caused breakdowns owed to lubricant contamination by combustion byproducts. This especially affected camshafts and lifters, for Olds used severe valve actions to get the best combination of performance with quietness. Bearings failed, sometimes because owners failed to use the specified diesel-grade oil.

Task forces proliferated as Olds engineers and service people worked around the clock to get on top of the problems. A "water in fuel" warning light was a necessary Band-Aid while basic changes were made, including the installation of a separator to take water out of the fuel. A new cylinder block, the DX, dealt with many of the faults, fitted as it was with a new camshaft with roller lifters. This allowed the oil-change interval to extend to 5,000 miles.

By the early 1980s Oldsmobile was building entirely serviceable diesels. Thanks to Lansing's experience and lengthened testing, its V-6 was a good engine from the get-go. Later V-8s had phenomenal durability, some lasting 400,000 miles. But the early ones were so bad that GM suffered the ignominy of a class-action lawsuit by the Naderite Center for Auto Safety that concluded with an FTC-supervised program that compensated owners up to 80 percent of the cost of a new engine with no time or mileage limits on failures.

In spite of its problems, in 1982 Oldsmobile alone had one-third of the US market for diesel-powered cars. But the demand for diesels was diminishing. While America was coming out of its early-1980s recession, OPEC opened the gasoline spigots. Seizing the moment, unenlightened authorities slapped more taxes on diesel fuel. By then, wrote one historian, "while people loved diesel economy, they didn't like clattery engines, reduced performance, longer starting times, the smelly fuel or having to fill up at truck stops." Diesel cars also cost extra, an added deterrent.

By the time Oldsmobile stopped making diesels mid-way though its 1985 model year it had produced more than a million. The very public problems had hurt, to be sure, but the real reason GM exited the American diesel market was that the demand for diesels had faded. This hit all those trying to sell diesel cars in North America, not just Oldsmobile.

Now it's time for a diesel comeback. As I said in Winding Road Number 25, the potential range of fuel-economy "improvement by dieselization is 15 to 40 percent. In fact it's the only available technology that offers double-digit cuts in fuel consumption. The emissions problems of diesels have to be solved - as they can be. As the Partnership for a New Generation Vehicle concluded, diesel engines are the way to go."

With diesels at all sizes of cars offering outstanding performance with great fuel economy, it's hard to argue against them. All they lack is the sex appeal that's been so beneficial to hybrids. This is coming. Subaru has produced a diesel version of its traditional flat four, while Honda has plowed its own diesel furrow with excellent results. The VW Group has made a major commitment to diesels. And if its Audi R8 V12 TDi isn't sexy, I don't know what is.

Powered by a twin-turbocharged 6.0-litre V12 diesel, Audi's R8 is thrust toward the horizon by 500 bhp and 737 lb-ft of torque. It's said to have a 0-62 mph time of 4.2 seconds and a top speed "well over" 186 mph. Maybe this is the kind of projectile we need to give Doctor Diesel's great engine the respect that causes more than half the new cars in Europe to be diesel-powered. It's the least we can do for the great pioneer whose 150th birthday we celebrated last March 18th.

- Karl Ludvigsen

Capturing a Leaping Cat in Metal

The new Jaguar XF, a gift from Ford to the luxury-car maker's next owner, finally cracks the code of a suitable style for future cars from the leaping cat. We take an inside look at Jaguar and its past and present design techniques.

After Ford bought Jaguar I visited its executives to drum up business for my management-consulting company. One of my ideas was the creation of a "Jaguar Bible". This would be a guide to the way that Jaguar did things, to the distinctive methods that contributed to the special character of this most British of executive-car companies, techniques that would be alien to the minds of the Ford executives taking over. Needless to say they turned me down. "We know all about that" was the thrust of their reply.

We are approaching twenty years later with Ford never having cracked the Jaguar code. I'm reminded of the comment by William Clay Ford when he was asked how soon Jaguar would be in the black. "Well," he replied, "it took forty years for Lincoln to make a profit. I hope it doesn't take as long with Jaguar!" Now it will be up to someone else to solve the puzzle of Jaguar, with Ford having decided to see the back of one of the world's most prestigious car brands.

Styling has been at the heart of Jaguar's special appeal to the pocketbooks of car buyers the world over. There have been bad Jaguars, but it's not easy to think of ugly Jaguars - certainly not during the years to 1972 when the company's founder, Sir William Lyons, had the final word about the way Jaguars looked.

The was a reason why Jaguars had a special panache. Although William Lyons was effectively chief stylist as well as chief executive, he was no artist. He didn't sketch or draw design suggestions. Rather, Lyons worked in the form of full-scale steel models. His craftsmen shaped panels in the usual way and mounted them on a wooden frame so they served as a visible mockup of the future design. After Lyons reviewed and critiqued the mockup the responsible workmen revised the shapes and presented their proposals again to Lyons.

Lyons worked with one or two selected panel beaters, men who had a particular sympathy with his ideas. When the metal mockup was ready for review it would usually be assembled in Sir William's front drive at home. This allowed him to see the shapes in the daylight, in the open air and in the kind of surrounding in which the car would eventually be judged. Only after he had approved such a metal mockup would the final drawings and engineering for production be carried out.

This design method meant that Jaguar shapes were fully compatible with the use of sheet metal. This typically gave Jaguars a crisp, light, metallic skin that lacked the excessive curvature or over-wrought look that sometimes results when shapes are modeled in clay for their own sake by designers who aren't respectful of the demands of sheet metal as a body material.

By necessity this method of working was progressive rather than spectacular. Thus the designs of Jaguar models tended to evolve gradually rather than making sudden leaps from one form to another. The Lyons method tended to give continuity to the Jaguar design patrimony, which it did with great success.

Nevertheless the Lyons Jaguar was capable of making big leaps in design when its leader sensed that the market demanded it. After his transitional Mark V Lyons segued smoothly into the full-fendered era with 1951's Mark VII. While this evolved into the "big" Jaguar. Lyons sensed a need for a smaller and less expensive sedan. He filled this gap with the 2.4 Litre launched in 1955. Powered by a short-stroke version of the famous twin-cam six, this was Jaguar's first integral body/frame car. Its styling was sleek and compact, strikingly different from the bigger and more costly Mark VII.

Here, if heeded, was a clear lesson from the "Jaguar Bible" for the Ford managers tasked with taking Jaguar forward. However, when they introduced the S-Type and X-Type they aped, on a smaller platform, the styling characteristics of their predecessors. They should have searched for a new idiom, as William Lyons did, that would appeal to a more youthful owner body. Instead they flew in the face of the well-known car-industry axiom that you can sell a young man's car to an old man, but you can't sell an old man's car to a young man.

Through these crucial years, from 1984 to 1999, Jaguar styling was in the hands of Geoff Lawson. Although a purebred Briton, the mustachioed Lawson was a passionate fan of American cars in general and Corvettes in particular. Among his many other interests were guns and shooting, designing and playing guitars, mountain biking, abstract art and sculpture. A strong personality, Lawson saw his role as a custodian of the Jaguar tradition in design. He showed this with the evolutionary XJ8 sedans and the XK8 sports coupe of 1996. Although clearly indebted to the E-Type, the latter was demonstrably the finest Lawson Jaguar.

New to the Jaguar styling team in 1999 was Scotsman Ian Callum. Like Lawson a graduate of the Royal College of Art, he spent 11 years at Ford, contributing to the RS200, Escort Cosworth, Fiesta and Mondeo. In 1990 Callum left to set up a new design studio for Tom Walkinshaw's vehicle engineering group TWR. "Some of my colleagues came to see me from Ford. I'd walked away from this giant studio at Dunton, the corporation, all that stuff, into this little tin shed in Kidlington. They thought I was utterly mad. But I was as happy as could be. I was doing something I wanted to do."

Car fanatic Callum shaped body kits for TWR-converted Mazdas and Holdens. He then hit the big time when TWR was commissioned by Ford to design and build the Aston Martin DB7, which was launched with great acclaim for its styling. Further Astons and a variety of other projects for TWR followed. In 1999 Callum came back into the Ford fold to set up an advanced-design studio for Jaguar, only to be named the company's styling director when Geoff Lawson unexpectedly died aged 54.

For a while Callum directed design for both Jaguar and Aston Martin. He has clear ideas about the differences between the two makes. "Jaguars are more voluptuous than Astons, more curvaceous, more extreme. They shout a bit louder than Astons." The E-Type, he says, is the perfect example. "Though it was a beautiful car it was quite a statement. Visually it's shouting at you. You couldn't get more ostentatious than the E-Type."

Another earlier Jaguar, the original XJ6 sedan of 1968, was a big influence on Ian Callum. "I just stared at it and stared at it, literally for hours on end," he says. "Basically it's where I learned about the proportions of a car. The wheels were enormous and there's this lovely lean piece of metal above them. Gorgeous. That was Lyons. He just knew how to do this."

But Callum knew that aping the past wasn't the path to the future for Jaguar. He wanted to create a Jaguar for the 21st Century. But to do this he had to win over Ford managers who were nervous abut tinkering with the iconic Jaguar look, even though markets were telling them it wasn't working. The company had been heavily criticized for introducing a new XJ in 2002 which used radical new aluminum technology for its unit body but looked little changed from its predecessor.

"I had to convince them that there was more than one way to skin a cat, so to speak," said Callum of his managers. To achieve this he had to raise his own game, he admitted: "I never considered being number one, but I was offered the best job in the world and I was terrified. I had never wanted to be promoted into a position where I'd be expected to make public speeches. I also had to learn how to manage people and a whole department. My initial problem was naivetť. I didn't know how to run a department of 100 people. I wasn't an executive and I had to learn the processes." As well he had to learn how to communicate to a board that had proven that it was nervous about styling: "I had to learn how to verbalize what Jaguar was all about: good taste, good design and drama."

Concept cars were the way, Ian Callum decided, to gain fresh perspectives both inside and outside Jaguar. "I wanted to make a statement about what a Jag could look like that wasn't what you'd expect. It was a ploy to convince people that a Jaguar didn't have to be a stereotyped vehicle, as it's been in the past." He showed this with the R Coupe in 2001 and then with the R-D6 unveiled at Frankfurt in 2003. With the latter, said Callum, "I wanted to produce something that was very difficult to define. People didn't know whether it was a coupe or a hatchback or a saloon car or a sports car. They couldn't work it out. That's great!

"Jaguar adhered to the rulebook of what a Jaguar is for too long," Callum said in 2005. "The next stage is to throw the rulebook away completely - because that's what Lyons would have done." Indeed, as we've seen that's just what Lyons did when necessary. And it's what Callum had his team did with the new Jaguar XF sedan, which won justly-deserved plaudits for its sharp new style both inside and out. It's the replacement for the S-Type and sits on a development of its chassis, so they could have called it the XS - but I suppose they didn't like the way that sounded!

The new rulebook - the "Jaguar Bible" for the 21st Century - seems to be taking shape. If India's Tata takes over Jaguar together with Land Rover, as seems likely at this writing, it will further liberate Callum and his colleagues to fashion new Jaguars that will deserve serious consideration by those for whom Germany's domination of the executive-car sector is increasingly unedifying. Why didn't it happen on Ford's watch? I think I've given you some clues.

- Karl Ludvigsen

Porsche Was Right - Twice

Front-wheel drive has enjoyed a long run as the layout of choice for small cars. But it's not without disadvantages as engineers in Japan, Germany and India - yes, India! - have decided. The auto industry's next step is to the rear.

The overwhelming new trend in small-car design, already visible through the haze, came into high-definition focus at the end of last year. Engines are marching to the rear. This brings an eerie echo of the 1950s, when the most popular small cars were rear-engined. Fiat's 500, 600 and 850, Renault's Dauphine and Volkswagen's Beetle all had engines between their rear wheels. The merits of the layout even led Chevrolet to build its Corvair in America and Hillman its Imp in Britain.

Then in the 1960s front-wheel drive became the rage. Led by the Mini of Alec Issigonis and the Fiat and Autobianchi designs of Dante Giacosa, engines were mounted transversely up front to power the front wheels. Power packages were still integral, with engines attached to transmissions and axles, but now in the front instead of the rear, a change made possible by better tires and universal joints.

Generations of drivers soon got used to the new paradigm. Handling and stability were good, thanks to the weight forward, though a well-equipped car needed power steering. Also the steering wheel sometimes seemed to have a mind of its own thanks to the phenomenon known as "torque steer". Front-tire wear could be heavy while braking needed careful tailoring owing to rear-wheel lightness when the car wasn't heavily laden. A much-touted advantage of front-wheel drive, the elimination of a central floor tunnel, wasn't actually achieved in practice. The exhaust and controls had to go somewhere.

Now engineers who've taken a fresh look at the small car have decided that rear engines weren't such a bad idea after all. In 1992 we had a glimpse of the future in GM's Ultralite, which had its two-stroke engine in the rear. In 1994 Mercedes-Benz unveiled its involvement in the Smart project and showed two small-car studies of its own, both rear-engined. When the Smart ForTwo came to market in 1998 its rear-mounted engine was the most unusual feature of a very unusual car.

Meanwhile at a car-development center at Okazaki in Japan's Aichi prefecture auto engineers were mulling over the design of a new entry in that country's intensely competitive Kei class of small cars. So important is it that of the 3.7 million cars sold in Japan in 2006, 2.0 million or 55 percent were Kei cars, limited to 660 cc engines and a maximum length of 3.4 meters or a little more than 11 feet. Here was a real challenge for designers. How could they pack the most space and value into this specification? That's what Mitsubishi needed to find out.

The first sign of their conclusions was the "i" concept car that appeared at Tokyo in 2003. It was a four-door car with MacPherson strut front suspension and a de Dion rear axle. Its newly developed three-cylinder engine was positioned just above and forward of that axle, nestling low behind the rear seats. That this was more than a pipe dream was shown by the introduction of the i as a production model in 2006. The following year it went on sale in selected markets abroad.

Mitsubishi's Shinsuke Kawamura, who played a key role in the i's creation, pointed out that the rear engine brought a number of advantages, including:

- No need for power steering in the base model.

- Freedom from torque steer.

- A better turning circle in combination with a long wheelbase and large wheels.

- Great flexibility for the development of more models on the same platform.

- Adequate front and rear crash-energy absorption compatible with a long interior compartment.

Kawamura-san could have added that with front/rear weight distribution of 45%/55% braking effort was shared more evenly among all four wheels, increasing their stopping power. Drive traction was excellent as well.

Many of these considerations were in the mind of Ferdinand Porsche when he conceived the famous Volkswagen Beetle. While others had tinkered with rear engines, Porsche was the first to make a practical rear-engined small car in volume. His pre-war KdF-Wagen - as it was known then - was the inspiration for the Fiats and Renaults. Thus it's significant that at the end of 2007 the company he co-founded announced its plans to introduce a new range of rear-engined small cars "before the end of the decade".

In concept form Volkswagen unveiled its "up!" as a two-door at Frankfurt and then in four-door form, with a longer wheelbase, at Tokyo. It was the joint effort of Ralf-Gerhard Willner, in charge of concept development, and chief designer Walter de Silva. Their work, they said, involved "a hard clash of ideas between engineers and designers. That is the only way to produce icons." They deliberately aimed for a look of raw functionalism which they described as "A clever innovative wholeÖa friendly and masterful car."

So far VW is coy about the up!'s technical details, saying only that its engine is in the rear. It could do worse than to recall the concept that the Porsche company designed for it in 1969-70. VW chief Heinz Nordhoff launched Ferry Porsche and Ferdinand PiŽch on the assignment to deign a Beetle successor before his death in 1968. His successor Kurt Lotz asked the Porsche men to push ahead with the project that was Type 1966 to Porsche, EX266 to VW's engineers and Type 191 as the production model it was intended to be.

The Porsche layout was radical. The in-line water-cooled four was placed longitudinally in front of the rear axle, lying horizontally to the right. In the space to its left were its radiator and fan. In this "under-floor" layout the engine was placed well forward, actually under the rear seat, with a four-speed transmission between it and the final-drive gears. This meant that top gear could be a quiet and efficient direct drive. The under-seat engine meant that passengers in the rear sat higher than usual, which as Porsche pointed out gave them a better view, especially with America's mandated front headrests.

Anything as radical as an under-floor engine was bound to attract its critics. One was a VW engineer who had formerly designed submarines. "What about water on the engine?" he asked. This so irritated Ferdinand PiŽch that he ordered a huge tub to be built in which the entire prototype was immersed. "It started under water," said an observer.

As a final pre-series for testing Porsche built 100 engines and 50 gearboxes of the Type 1966. In four development stages some 50 complete vehicles were made in 1970 and into 1971, 15 of these made by VW itself. Preparation of production tooling was under way when, in the autumn of 1971, Kurt Lotz suddenly and unexpectedly left the company. He was succeeded by Rudolf Leiding, who decided to cancel Porsche's project and instead to plunk for the layout of 1969's Car of the Year, Fiat's 128. Creation of the Golf was an important step in the rise and rise of front-wheel drive. Thus Porsche and Ferdinand PiŽch - both deeply involved with VW these days - have unfinished business in the rear-engined small-car arena.

The latest indication that engines in the rear are making a comeback came on January 10th in New Delhi, India. There to intense enthusiasm Ratan Tata unveiled his Tata Nano, designed and tooled to sell in its most basic form for about $2,500. Conceived as a gap-filler between motorcycles and India's smallest cars, the Nano is set for production at better than 250,000 a year at Tata's factory in Bangladesh. It's a cheeky four-door sedan designed by 500 of the company's own engineers with the help of Turin's IDEA Studio, long-time consultant to Tata.

With its standard CVT transmission, the Nano's 624 cc twin-cylinder engine is smack between the little car's rear wheels. It's a layout that provides remarkable spaciousness in a car only two inches more than ten feet long. Tata took a leaf from the book of Alec Issigonis by giving its Nano four tiny wheels at its corners, providing maximum stability with minimum intrusion on its interior. Though designed to meet India's needs, the Nano is scheduled to be exported in a less austere version once initial domestic demand has been satisfied.

Those are the first indicators of this new trend. One other point is strongly in favor of rear engines for small cars: the layout is ideal for alternative forms of power. Up front, between the wheels, space is limited for all the gubbins needed by an electric or hybrid drive train. At the rear there's plenty of room to accommodate these new low-emissions power trains. In fact Mitsubishi has already launched a trial fleet of the MiEV electric version of its i, with batteries under the front seats. Sounds like an idea whose time has come!

- Karl Ludvigsen

Setting Sun in Formula 1

When Honda engines were powering McLaren and Williams Grand Prix cars to wins in the 1990s it seemed that the Japanese were taking over the sport. Now that they're building and racing their own cars, however, the outlook isn't so bright.

Honda's Formula 1 team had cause to celebrate at the end of the 2007 season. They won a Grand Prix, their first of the year. It wasn't on the track, however. Honda received the "Green Awards Grand Prix" presented by a judging panel set up by the United Nations Environment Program as a means to "recognize outstanding creative workÖfor brands promoting anything from fair trade and renewable energy to resource efficiency and waste awareness."

In its sphere this was a pretty big deal. The Honda team's environmental initiative, its www.myearthdream.com website and the swathing of its cars in huge decals showing the surface of the earth combined to win its nominated category of Best PR Campaign with a budget of over £100k against strong competition from Marks & Spencer and Procter & Gamble. Then with the other category winners Honda Formula 1 went into the final judging for the Grand Prix - and won. Honda's was judged "the campaign which best exemplified an outstanding environmental message and had the greatest capacity to raise awareness amongst the general public."

In less elevated terms Honda reaped what one publication called an "image disaster" from its unconventional Formula 1 livery. When it was launched at the beginning of the year its earth-like look was widely lambasted as bizarre, inappropriate, illegible and even ugly. Nor did it yield recognition on the track, imparting a strange look to the RA107. As well its lack of clear identity logos won Honda the last place in an image-recognition survey of Formula 1 at mid-season.

Also scuppering Honda's attempts to gain visual recognition for its "green" imagery was its cars' appalling performance on the track. For Jenson Button it wasn't enough to be eclipsed by meteoric newcomer Lewis Hamilton. He became the forgotten British star, mooching about at the back of the field with team-mate Rubens Barrichello, once a race winner for Ferrari.

In 2007 Honda ranked eight in the championship of makes table with a measly six points. As a nadir this was comparable only to the seven points it scored in 2002, its third year as an engine supplier to British team BAR. BAR-Honda did wonderfully in 2004 with 11 podiums on the way to second in the championship with 119 points. This was a tribute to the design skill of Briton Geoff Willis, whom BAR had poached from Williams.

In 2006 Honda took over the BAR team and began sailing under its own banner. It did well, scoring one lucky win for Button and compiling 86 points for fourth place in the makes rankings. Mysteriously, however, it dispensed with the services of Geoff Willis in mid-2006 after a former Honda motorcycle-racing engineer was promoted above him. The 2007 results suggest that this was not Honda's smartest move.

The Japanese, it seems, had taken against Willis's style of firm direction from the top. "He wasn't very well liked by the resident Japanese engineers," said an insider, and as a result was subjected to a witch hunt. In the BAR days, said my source, "there was a room with 60-odd Honda engineers linked to the CAD system. They had full access to view the drawings but the IT system wouldn't accept any uploading of drawings from the Japanese section, it having been made quite clear to them that they were there to look but not touch."

Only weeks earlier in 2006 the other Japanese car-maker team in Formula 1, Toyota, had released its high-profile technical director, Mike Gascoyne. Toyota started its Grand Prix team from scratch, converting and expanding its former rally headquarters at Cologne, Germany and staffing it with experts from many countries and companies. Starting in 2002, its results in the first two season were mediocre with 16 points or eighth place in the championship in 2003.

At the end of 2003 Toyota hired Englishman Gascoyne, who had a well-deserved reputation for turning struggling teams around with a tough regime. He'd done that for Jordan from 1998 to 2000 and for Renault through 2003, giving them winning form. At a reputed salary of $6.5 million he led the design of Toyota's TF105 for the 2005 season, taking the team to fourth in the championship with 88 points, two pole positions and five podium places.

The TF106 started the 2006 season slowly, however. Chafing under Gascoyne's dictatorial rule, Toyota's Japanese masters agreed his departure in April of 2006, saying that he left "amicably" after a "fundamental difference of opinion with regard to the technical operations" of the team. Having established its Formula 1 team based on "the wrong brief, premises and personnel," said my insider friend, "the hiring of Gascoyne was just an example of the credo that if you throw money at it, it will eventually work."

So how has Toyota fared subsequently with its more collegiate approach, without an experienced big-name technical director? In both 2006 and '07 it was sixth in the makes championship, this year with a paltry 13 points. Like Honda, Toyota ranked a place higher than it deserved this year by virtue of the docking of all the makes points of McLaren-Mercedes after the discovery of its use of confidential Ferrari information. Although fielding having competent drivers in Jarno Trulli and Ralf Schumacher, Toyota had not a sniff of a podium in its sixth season of 2007, let alone a win. Saying "sometimes thinks in life don't work out the way you expected them to," Ralf left at the end of the season.

In spite of results so far that give new meaning to the word "mediocre", Toyota declares its intention to press on. In fact Kazuo Okamoto, its executive vice president for research and development, forecasts a win in 2008. "Motorsport is all about dreams and passion," he said. "We will not pull out just because we haven't won a race. F1 is an important development ground for Toyota." In the Formula 1 of the future, he added, "there are development opportunities for using hybrid technologies and bio-fuels."

Nor does Honda envision a withdrawal. Like Toyota, it relishes rubbing shoulders in the paddock and on TV screens with upscale brands like BMW, Ferrari and Mercedes-Benz. Its purpose, said Honda's Yasuhiro Wada, is "a mixture of engineering challenge and also carrying on the racing heritage which is connected to the Honda brand. Obviously, nowadays we have to think about some marketing aspects of the Formula 1 society as well." Hence the myearthdreamô concept.

Somewhere in this corporatespeak something's missing - a clear commitment to win races and championships. In the Japanese teams, says an engineer who works with them, "all the major decisions will be taken by a committee after a lot of horse trading on spheres of influence, attributes and roles. The actual business at hand will not be high on the list of priorities. This bodes ill for decisive moves on racing decisions or even for a clear direction continuously pursued. They will chop and change with the wind.

"At Honda and Toyota there are many 'project leaders'," adds the engineer, "senior this or that, but fundamentally they're all kept in check by a informal peer group. Within this they have to maintain good relations and accommodate the thoughts of others. Anyone standing out from the group will be hammered down. They are not very good at accepting forthright comments or dissension, which explains why Gascoyne had to go.

"A technical director or chief designer goes against the Japanese tradition of anonymous group work," says my insider. "They're very good at smothering everything under meetings and reports ad-infinitum, plus the ever-popular 'counter-measure' to solve the problems caused by indecision and fumbling along. Add to this a no-blame (at least for the Japanese) culture that sweeps everything under the carpet and ignores it.

"Despite the generous finance available," concludes my source, "a fully Japanese-managed team will never win a world championship and never has, be it in motor racing, ping pong or rose growing, because they will never take any action and assume the blame if it doesn't work. The modus operandi is to wear belt and braces and keep sitting down to make sure one's pants don't fall down, plus procrastinate and delay decisions until there is only one way to go. Therefore no-one is to blame because that was the only possibility left."

Moreover, adds my insider, bringing in foreigners is seen as a last resort. "The Japanese view all gaijin as barbarians and assume that they can do it better, despite ample evidence to the contrary, and only deal with foreigners under duress or extreme need." That Honda has come to realize that its dire situation constitutes duress and extreme need is shown by its appointment of Britain's Ross Brawn as its new team principal, effective November 26th. He first visited the factory in Brackley two weeks earlier.

Honda has trusted its fate in racing to gaijin before. It entered Formula 2 in Europe with Jack Brabham's team and called on John Surtees to help it in 1967, when it scored a lone win with its engine in a Lola-derived chassis. Since then Honda engines have performed well, for McLaren and Williams among others, but building a complete car and running the racing team are tasks of an altogether higher order of magnitude - as the Japanese are discovering.

Now with the hiring of Ross Brawn Honda has set aside its pride - indeed arrogance - to hire the bespectacled 52-year-old whose Ferraris won six constructors' championships in a row from 1999 to 2004. From the end of 2006 Brawn has been on sabbatical from Ferrari. "I miss the racing a lot," he found. "I miss the sport. I miss the teamwork. I miss being part of a group of people who achieve something that is very difficult but when achieved is very rewarding."

Brawn's arrival will buck up Rubens Barrichello, who raced for him at Ferrari and has just suffered an excruciating season in which he scored no points. "It's the best thing that's happened in a long time," said Britain's forgotten speed merchant, Jenson Button. It looks like one Japanese team, at least, is starting to take Formula 1 seriously.

- Karl Ludvigsen

Abarth Back in Action

When I first wrote about Abarths I called them "Tiny Tornadoes from Turin". The name still suits a promising revival of one of the most dynamic brands in automotive history.

What qualifies a moribund marque for a second coming? The answer boils down to category, content and charisma. Its image has to suit the category into which a car maker or entrepreneur wants to introduce a new product. It must suggest a technical and stylistic content that suits that category. And it must have charisma, that ineffable attribute that excites love and longing in the potential customer. On all three criteria Abarth scores big time.

So why has Fiat's Abarth brand been "resting" - as they say in the acting trade - for several decades? Why was such a valuable asset for a maker of small cars allowed to languish unloved? Blame it on a revolving door of top and medium managers who lost track of what made Fiat's cars appealing. They kept the distinctive scorpion badge alive in a desultory way, slapping it on variants willy-nilly much as Ford still deploys its deeply devalued Ghia badge in Europe.

Now Abarth is reviving big time. The company is being set up again in its traditional and historic quarters on Turin's Corso Marche. Its staffing of 113 includes 26 engineers, 43 production experts and a team of nine dedicated to motor sports participation. I know these buildings well, having visited Abarth in the late 1950s and early 1960s and several times at the end of the 1970s when they were preparing two special 131 Abarths for us at Fiat to enter in the SCCA's rally championship.

It was always a treat to visit Abarth because something exciting and interesting was bound to be happening, be it a new twin-cam engine on the dyno, a record-breaker under construction or a new sports-racer being completed. The small quarters were always in perfect order. "If there's anything he hates," driver Hans Herrmann said of Carlo Abarth, "it's dawdling, disorder and dirt. The factory halls are almost as clean as a pharmacy. Materials, tools and cars have their designated places. He takes care that his cars go to the start sparkling." Abarth's 21st-Century successors have a lot to live up to.

They're off to a pretty good start. Abarth has been resuscitated by Lapo Elkann, the Agnelli descendant who looks after branding at Fiat, and Luca de Meo, in charge of the Fiat business, now a separate unit in the Fiat Group. They're kicking off with cars based on the well-received Fiat Grande Punto. Just launched in Europe is the car's Abarth sister, which uses a turbo to pump out 180 bhp, in the SS version, from only 1.4 liters. It's a spunky machine that is decisively badged as an Abarth - no Fiat identity anywhere.